Look closely or you might miss it. Heck, even with close inspection you still run the risk of overlooking it. At this time of year, finding a cranefly orchid (Tipularia discolor) can present a bit of a challenge. At other times of the year the task is a bit easier. If you can find one in bloom, however, you are rewarded with, a unique orchid experience.

For most of the year, the cranefly orchid exists as a single leaf, which is produced in the fall and lasts until spring. It is thought that this orchid takes advantage of the dormancy of its neighbors by sucking up the light the canopy otherwise intercepts during the growing season. Any of you curious enough to look will have noticed that the underside of this leaf is deep purple in color. This very well may be an adaptation to take full advantage of light when it is available. There is some evidence that such coloration may help reflect light back up into the leaf, thus getting more out of what makes it to the forest floor. Evidence for this, however, is limited. It is far more likely that the purple coloration are pigments produced by the leaves that act as a sort of sun screen, shielding the sensitive photosynthetic machinery within from an overdose of sun as intense sun flecks dance across the forest floor.

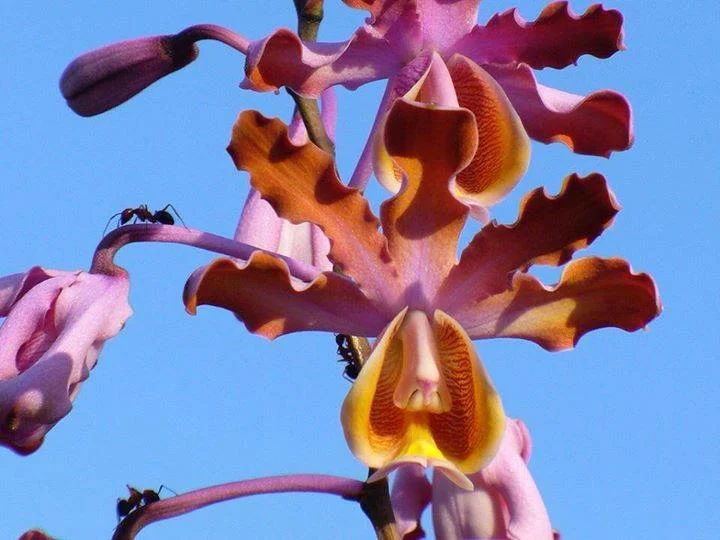

By the end of spring, the single leaf has senesced. If energy stores were ample that year the plant will then flower. A lanky brown spike erupts from the ground. Its purple-green color is subtle yet beautiful. The flowers themselves are a bit odd, even by orchid standards. Whereas most orchid flowers exhibit satisfying bilateral symmetry, the flowers of the cranefly orchid are distinctly asymmetrical. The dorsal sepal, along with the lateral petals, are scrunched up on either side of the column. This has everything to do with its pollinators.

The cranefly orchid has coopted nocturnal moths in the family Noctuidae for pollination. These moths find the flowers soon after they open and stick around only as long as there is nectar still present in the long nectar spurs. The asymmetry of the bloom causes the pollinia to attach to one of the moth's eyes. In this way the orchid is able to ensure that its pollen is not wasted on the blooms of other species.

As in all plants, the production of flowers is a costly business. Sexual reproduction is all about tradeoffs. It has been found that cranefly orchids that flowered and successfully produced fruit in one year were much less likely to do so in the next. What's more, the overall size of the plant (leaves and corms) were greatly reduced. Its hard to eek out an existence on the forest floor.

What I find most interesting about this species is where it tends to grow. Any old patch of ground simply won't do. Research indicates that the cranefly orchid requires rotting wood as a substrate. It's not so much the wood they require but rather the organisms that are decomposing it. Like all orchids, the cranefly cannot germinate and grow without mycorrhizal associations. They just happen to partner with fungi that also decompose wood. Such a relationship underscores the importance of decaying wood to forest health.