James Henderson, Golden Delight Honey, Bugwood.org.

In honor of my conversation with Anacardiaceae specialist, Dr. Susan Pell, I wanted to dedicate some time to looking at a member of this family that is in desperate need of more attention. I would like you to meet the dwarf sumac (Rhus michauxii). Found only in a few scattered locations throughout the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions of southeastern North America, this small tree is growing increasingly rare.

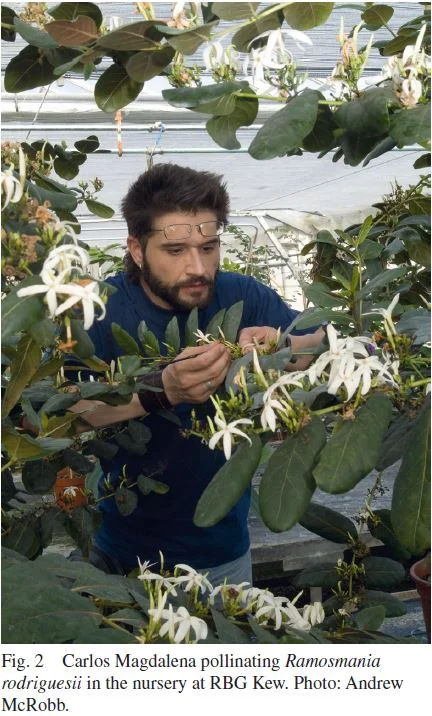

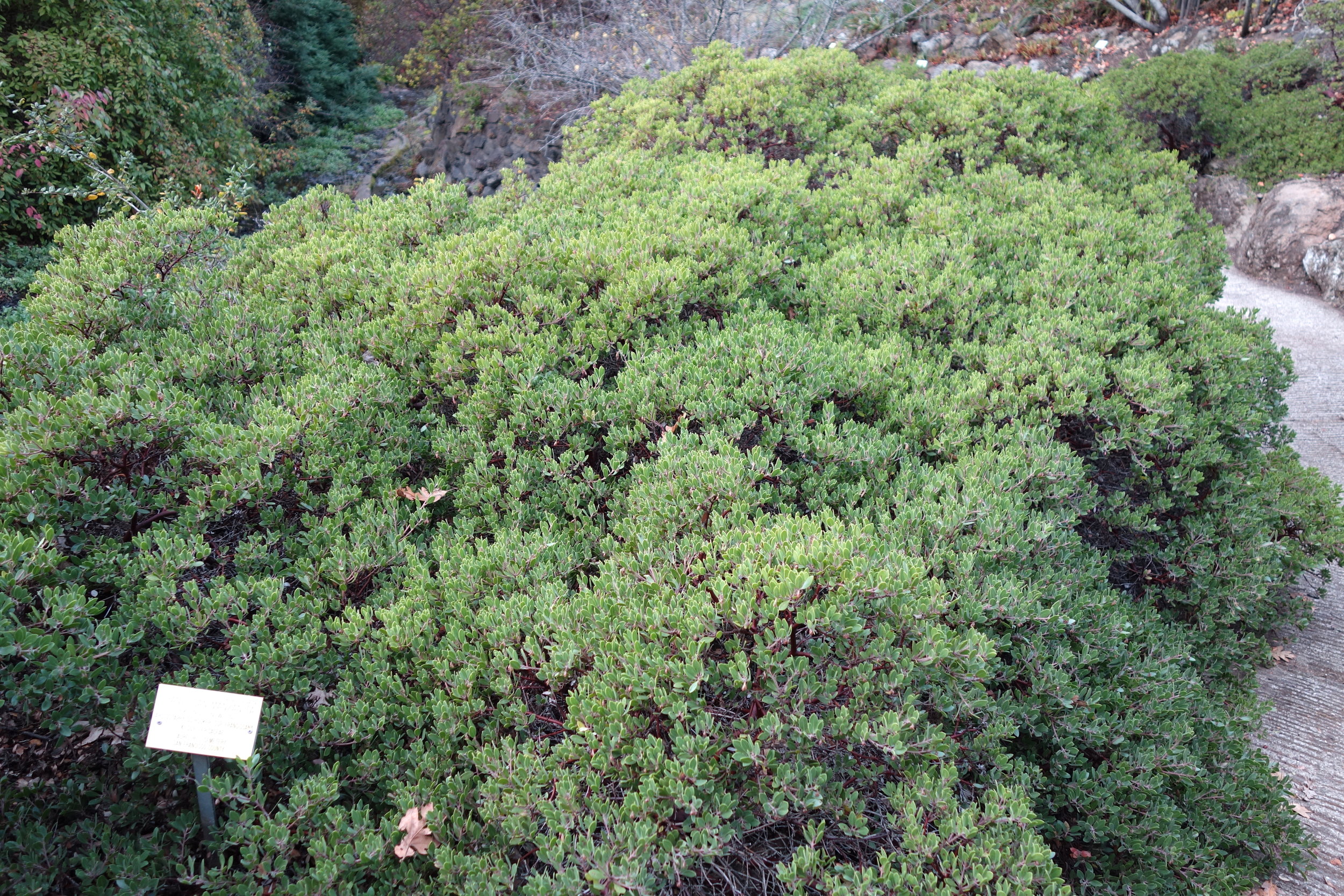

Dwarf sumac is a small species, with most individuals maxing out around 1 - 3 feet (30.5 – 91 cm) in height. It produces compound fuzzy leaves with wonderfully serrated leaflets. It flowers throughout early and mid-summer, with individuals producing an upright inflorescence that is characteristic of what one might expect from the genus Rhus. Dwarf sumac is dioecious, meaning individual plants produce either male or female flowers. Also, like many of its cousins, dwarf sumac is highly clonal, sending out runners in all directions that grow into clones of the original. The end result of this habit is large populations comprised of a single genetic individual producing only one type of flower.

Current range of dwarf sumac (Rhus michauxii). Green indicates native presence in state, Yellow indicates present in county but rare, and Orange indicates historical occurrence that has since been extirpated. [SOURCE]

Research indicates that the pygmy sumac was likely never wide spread or common throughout its range. Its dependence on specific soil conditions (namely sandy or rocky, basic soils) and just the right amount of disturbance mean it is pretty picky as to where it can thrive. However, humans have pushed this species far beyond natural tolerances. A combination of agriculture, development, and fire sequestration have all but eliminated most of its historical occurrences.

Today, the remaining dwarf sumac populations are few and far between. Its habit of clonal spread complicates matters even more because remaining populations are largely comprised of clonal offshoots of single individuals that are either male or female, making sexual reproduction almost non-existent in most cases. Also, aside from outright destruction, a lack of fire has also been disastrous for the species. Dwarf sumac requires fairly open habitat to thrive and without regular fires, it is readily out-competed by surrounding vegetation.

A female infructescence. Photo by Alan Cressler

Luckily, dwarf sumac has gotten enough attention to earn it protected status as a federally listed endangered species. However, this doesn’t mean all is well in dwarf sumac land. Lack of funding and overall interest in this species means monitoring of existing populations is infrequent and often done on a volunteer basis. At least one study pointed out that some of the few remaining populations have only been monitored once, which means it is anyone’s guess as to their current status or whether they still exist at all. Some studies also indicate that dwarf sumac is capable of hybridizing with related species such as whinged sumac (Rhus copallinum).

Another complicating factor is that some populations occur in some surprisingly rundown places that can make conservation difficult. Because dwarf sumac relies on disturbance to keep competing vegetation at bay, some populations now exist along highway rights-of way, roadsides, and along the edges of artificially maintained clearings. While this is good news for current population numbers, ensuring that these populations are looked after and maintained is a difficult task when interests outside of conservation are involved.

Some of the best work being done to protect this species involves propagation and restoration. Though still limited in its scope and success, out-planting into new location in addition to augmenting existing populations offers hope of at least slowing dwarf sumac decline in the wild. Special attention has been given to planting genetically distinct male and female plants into existing clonal populations in hopes of increasing pollination and seed set. Though it is too early to count these few attempts as true successes, they do offer a glimmer of hope. Other conservation attempts involve protecting what little habitat remains for this species and encouraging better land management via prescribed burns and invasive species removal.

The future for dwarf sumac remains uncertain, but that doesn’t mean all hope is lost. With more attention and research, this species just may be saved from total destruction. The plight of species like the dwarf sumac serve as an important reminder of why both habitat conservation and restoration are so important for slowing biodiversity loss.

Further Reading: [1] [2] [3]James Henderson, Golden Delight Honey, Bugwood.org.

![Current range of dwarf sumac (Rhus michauxii). Green indicates native presence in state, Yellow indicates present in county but rare, and Orange indicates historical occurrence that has since been extirpated. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1609184191069-557J58DPH2J8L74Y1O06/Rhus+michauxii.png)