Poop mosses are strange to say the least. They hail from the family Splachnaceae and most live out their entire (short) lives growing on poop. Needless to say, they are fascinating plants. Recently, one species of poop moss known to science as Tayloria octoblepharum was discovered growing in Borneo for the first time. As if this range expansion wasn’t exciting enough, their growing location was very surprising. Populations of this poop-loving moss were found growing in the pitchers of two species of poop-eating pitcher plants in the genus Nepenthes!

The pitcher of Nepenthes lowii both look and function like a toilet bowl. Photo by JeremiahsCPs licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License

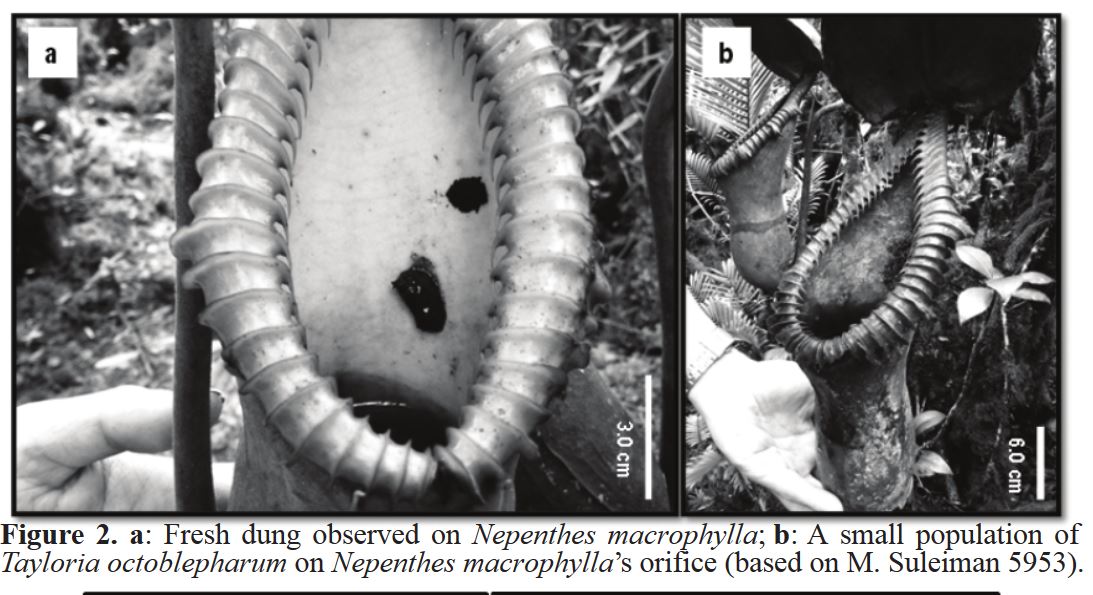

The wide pitcher mouth of Nepenthes macrophylla offer a nice seating area for visiting tree shrews.

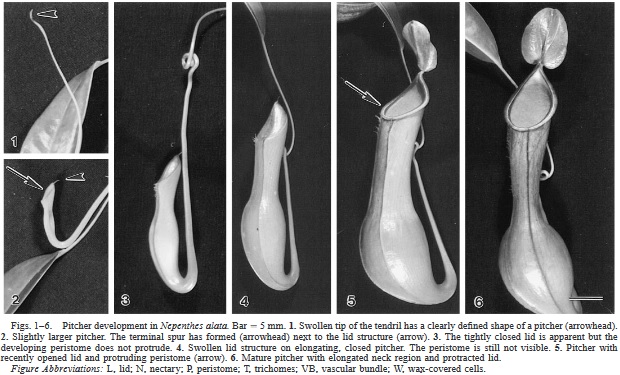

The pitchers of both Nepenthes lowii and N. macrophylla get a majority of their nutrient needs not by trapping and digesting arthropods but instead from the feces of tree shrews. They have been coined toilet pitchers as they exhibit specialized adaptations that allow them to collect feces. Tree shrews sit on the mouth of the pitcher and lap up sugary secretions from the lid. As they eat, they poop down into the pitcher, providing the plant with ample food rich in nitrogen. Digestion is a relatively slow process so much of the poop that enters the pitcher sticks around for a bit.

During a 2013 bryophyte survey in Borneo, a small colony of poop moss was discovered growing in the pitcher of a N. lowii. This obviously fascinated botanists who quickly made the connection between the coprophagous habits of these two species. On a return trip, more poop moss was discovered growing in a N. macrophylla pitcher. This population was fertile, indicating that it was able to successfully complete its life cycle within the pitcher environment. It appears that these two toilet pitchers offer ample niche space for this tiny, poop-loving moss. If this doesn’t convince you of just how incredible and complex the botanical world is, I don’t know what will!

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

Further Reading: [1]