Do you smell that?

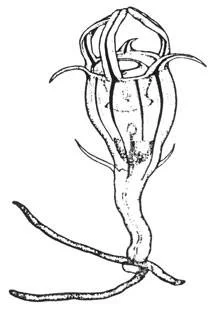

All around northeastern North America, a strange smell is starting to hang in the air. The skunky odor could easily be mistaken for an actual skunk but it isn't quite that strong. Some say garlic is a more apt description. If you are in a wet area you may notice small chimneys in the snow or what looks like a red and yellow parrot beak poking up from the ground. The smell gets stronger as you bend down to get a closer look. What you are seeing is Symplocarpus foetidus, better known as eastern skunk cabbage.

Skunk cabbage is a true spring wildflower. It is also one of those small groups of plants that can generate their own heat. This aroid can literally melt its way through the snow cover. Skunk cabbage hails from the same family of plants as the titan arum, Araceae. The inflorescence emerges in early spring, oten before the snow (if there is any) has had a chance to melt. Using heat generated via a unique form of metabolic activity, the inflorescence can reach temperatures of 15-25°C (59-77°F).

So, why the heat and smell? Well, if you like to bloom before the snow melts, you better hope you can at least melt through some of it. In deeper areas, skunk cabbage flowers create chimneys in the snow, which helps channel the scent up into the air. Though it may seem surprising, there are in fact insects out and about during the early days of spring. The smell attracts pollinators such as carrion flies and gnats. The heat also aids in volatilizing the odor, thus causing it to spread out farther. By blooming this early, skunk cabbage assures that its flowers get a majority of the attention.

After flowering is finished, the plant then throws up its large, green, elephant ear leaves. They are unmistakable. As the plant continues to grow throughout the season, its roots contract into the soil, digging the plant deeper and deeper. In effect, skunk cabbage grows down, not up. This is advantageous if you live in an area prone to flooding. The deeper you go, the harder it is to get pulled out.

I love this plant. It is wonderful to see its blooms poking up from underneath the snow. After so many months of drab colors and short days, this harbinger of spring is a breath of fresh, albeit stinky, air.