I was nibbling on some nori the other day when a thought suddenly hit me. I don't know squat about algae. I know it comes in many shapes, sizes, and colors. I know it is that stuff that we used to throw at each other on the beach. I know that it photosynthesizes. That's about it. What are algae? Are they even plants?

The shortest answer I can give you is "it depends." The term algae is a bit nebulous in and of itself. In Latin, the word "alga" simply means "seaweed." Algae are paraphyletic, meaning they do not share a recent common ancestor with one another. In fact, without specification, algae may refer to entirely different kingdoms of life including Plantae (which is often divided in the broad sense, Archaeplastida and the narrow sense, Viridiplantae), Chromista, Protista, or Bacteria.

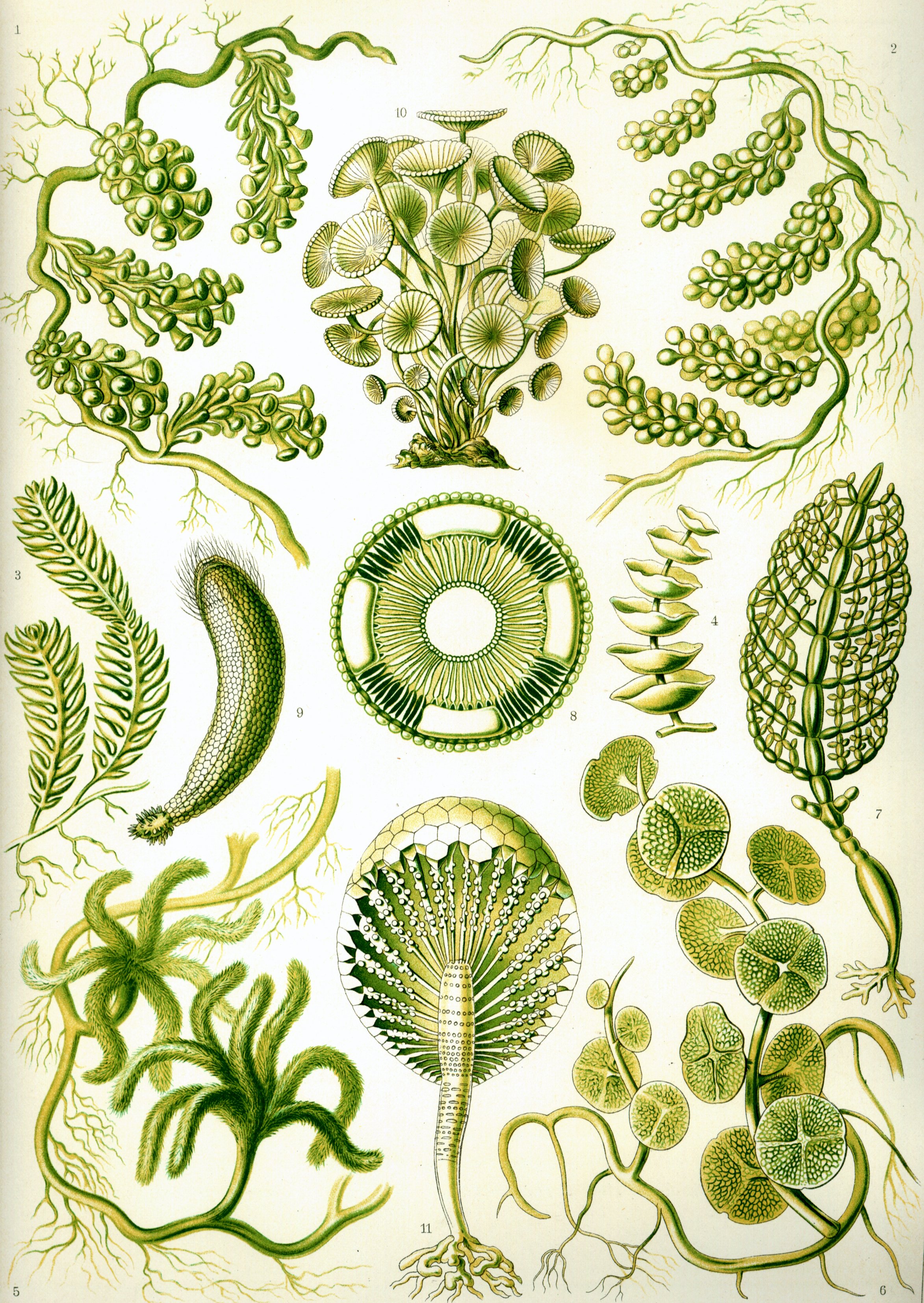

Caulerpa racemosa, a beautiful green algae. Photo by Nhobgood Nick Hobgood licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Taxonomy being what it is, these groupings may differ depending on who you ask. The point I am trying to make here is that algae are quite diverse from an evolutionary standpoint. Even calling them seaweed is a bit misleading as many different species of algae can be found in fresh water as well as growing on land.

Take for instance what is referred to as cyanobacteria. Known commonly as blue-green algae, colonies of these photosynthetic bacteria represent some of the earliest evidence of life in the fossil record. Remains of colonial blue-green algae have been found in rocks dating back more than 4 billion years. As a whole, these types of fossils represent nearly 7/8th of the history of life on this planet! However, they are considered bacteria, not plants.

Diatoms (Chromista) are another enormously important group. The single celled, photosynthetic organisms are encased in beautiful glass shells that make up entire layers of geologic strata. They comprise a majority of the phytoplankton in the world's oceans and are important indicators of climate. However, they belong to their own kingdom of life - Chromista or the brown algae.

To bring it back to what constitutes true plants, there is one group of algae that really started it all. It is widely believed that land plants share a close evolutionary history with a branch of green algae known as the stoneworts (order Charales). These aquatic, multicellular algae superficially resemble plants with their stalked appearance and radial leaflets.

A nice example of a stonewort (Chara braunii). Photo by Show_ryu licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

It is likely that land plants evolved from a Chara-like ancestor that may have resembling modern day hornworts that lived in shallow freshwater inlets. Estimates of when this happen go back as far as 500 million years before present. Unfortunately, fossil evidence is sparse for this sort of thing and mostly comes in the form of fossilized spores and molecular clock calculations.

Porphyra umbilicalis - One of the many species of red algae frequently referred to as nori. Photo by Gabriele Kothe-Heinrich licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Now, to bring it back to what started me down this road in the first place. Nori is made from algae in the genus Porphyra, which is a type of Rhodophyta or red algae. Together with Chlorophyta (the green algae), they make up some of the most familiar groups of algae. They have also been the source of a lot of taxonomic debate. Recent phylogenetic analyses place the red algae as a sister group to all other plants starting with green algae. However, some authors prefer to take a broader look at the tree and thus lump red algae in a member of the plant kingdom. So, depending on the particular paper I am reading, the nori I am currently digesting may or may not be considered a plant in the strictest sense of the word. That being said, the lines are a bit blurry and frankly I don't really care as long as it tastes good.

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

Further Reading: [1] [2] [3] [4]