Raise you hand if you have ever had a parlor palm (Chamaedorea elegans). I see most of you have raised your hands. Palms in the genus Chamaedorea are the most commonly kept palms on the market. They are small, very shade tolerant, and nearly indestructible. The clear winner in this regard is the parlor palm. We have all given these little palms a shot at one time or another. They are so common that we rarely give a second thought as to where they come from. Surely they did not evolve in a nursery. It may surprise you that for as ubiquitous as these palms are, they are actually quite threatened in the wild.

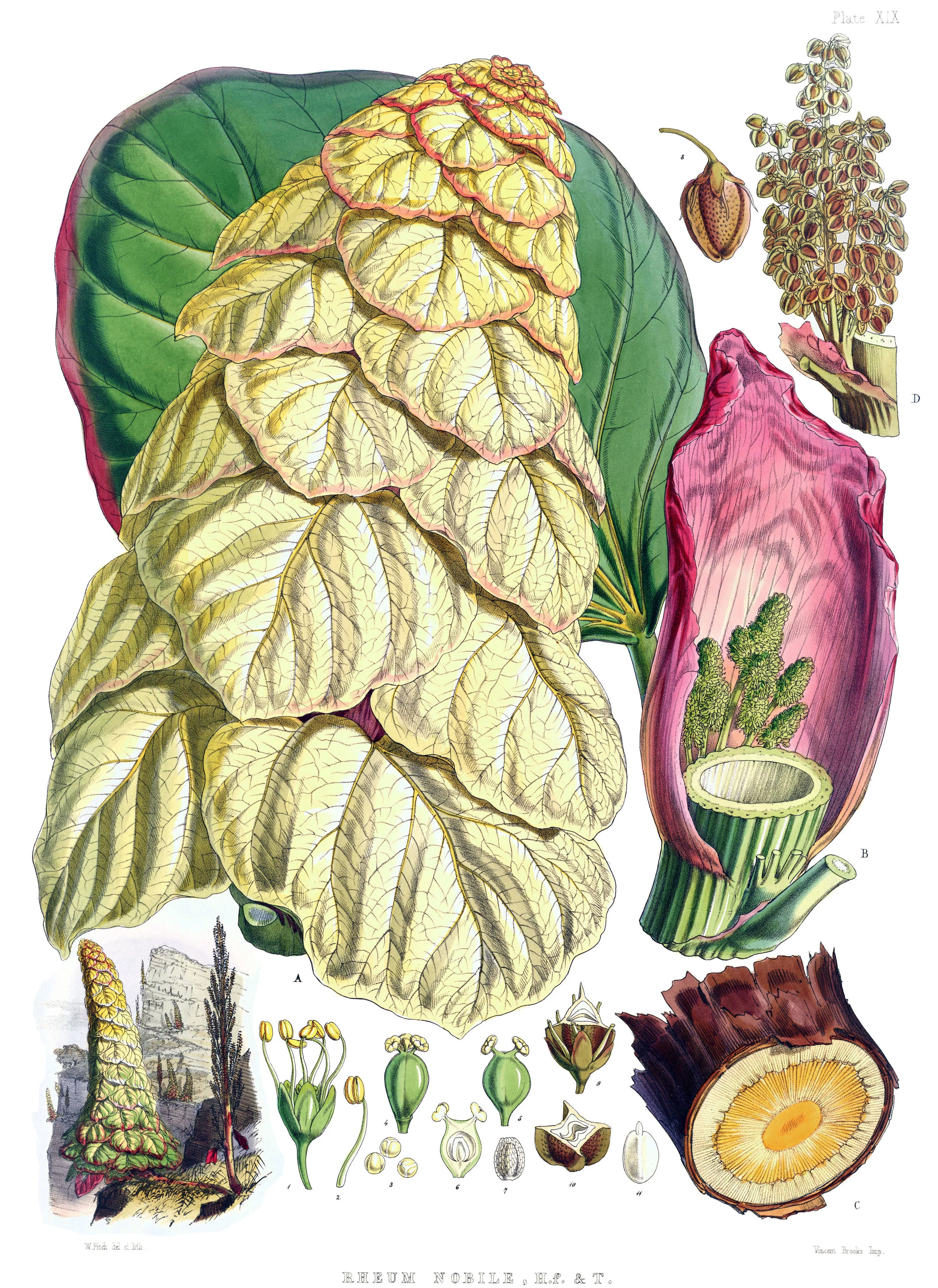

The genus Chamaedorea is endemic to sub-tropical forests of the Americas and is comprised of roughly 80 species. They are understory palms that are most at home under the deep shade of the canopy. Most species are generally pretty small, rarely growing over 10 feet. All of these factors add up to some resilient and fun houseplants. It doesn't take much to keep them happy. Every once in a while they will produce flowers. Though small, they are often brightly colored. The preferred method for mass cultivation is via seed. However, seed production outside of their native range is notoriously difficult and often requires human intervention. For this reason, a vast majority of nursery grown palms are grown from wild collected seeds.

This may not seem like a bad deal until you look at the numbers. I have seen reports of over 500 million seeds exported from Mexico annually. Couple this with the fact that many species of Chamaedorea are known to grow in very restricted ranges and suddenly the picture becomes very bleak. Over collecting of seeds has decimated wild populations. Without seeds there is no recruitment, no seedlings to take the place of adult plants.

Another considerable threat to these palms comes from the cut flower industry. Palm fronds are notoriously gorgeous and many people like to include them in their displays. Most of the leaves cut come from wild plants. Normally palm fronds are harvested in a manner that doesn't kill the plant, however, in Mexico children are often employed to collect them and their lack of experience can severely damage wild populations.

On top of all of this, the forests in which these palms grow are now being converted to agriculture. If actions are not taken to limit the abuse of wild populations, it is likely that some of the most commonly encountered house plants are going to be extinct in the wild. This is a hard pill to swallow. If you have any of these species growing in your home, take care of them. Perhaps knowing how uncertain the future is for many of these palms will earn them a little more respect.

Here is a list of some of the most threatened species in this genus:

Chamaedorea amabilis

Chamaedorea klotzschiana

Chamaedorea metalica

Chamaedorea pumila

Chamaedorea sullivaniorum

Chamaedorea tuerckheimii

Photo Credits: Michael Wolf (http://bit.ly/16suMsf), scott.zona (http://bit.ly/1zHdUII),

Further Reading:

http://bit.ly/1ADC3mw

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1542743921199-1RXQQYMY65FQF31CBRTH/en_2163.jpg)

![Matthew H. Koski & Tia-Lynn Ashman [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1421330939625-OA6DHYBZAK66BBJV71CW/image.jpg)