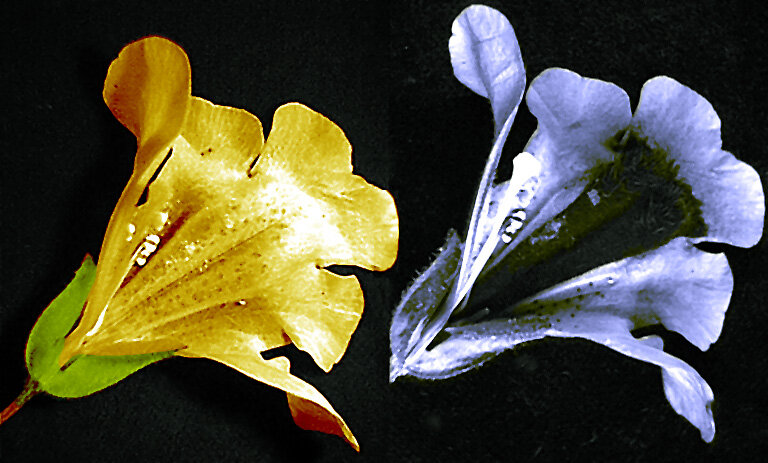

Photo by José María Escolano licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Plants go to great lengths to obtain the necessities of survival. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the desert regions around the world. Amazingly, myriads of plants have adapted to the harsh conditions that deserts offer up. Needless to say, water is a major limiting resource in these climates and many of the adaptations we see in desert plant species have to do with obtaining and holding on to as much water as possible. Some species get around the issue by going dormant whereas others stick it out using deep taproots that plug into the groundwater. A select few others hit the rocks.

Rocks? Well, gypsum to be precise. This interesting mineral is quite common in arid regions throughout the world. What is more interesting is that 20.8% of a gypsum crystal is water. Because of this, it has been suspected that gypsum in the soil could be a potential source of water for plants growing in these regions and a team of researchers out of Spain may have found just that.

Meet Helianthemum squamatum. This distant relative of hibiscus grows throughout the gypsum hills of the Mediterranean region. Unlike other desert plants, it is shallowly rooted. Unlike other shallowly rooted species, H. squamatum doesn't go dormant during the dry summer months. The physiology of this species in the context of the dry environments that it grows offers up quite a conundrum. How does this plant get the water it needs to grow through the hottest, driest months of the year?

By analyzing the isotopic composition of the water within the plant and comparing it to background sources, the team found that 90% of the plants water intake during the dry summer months comes from the crystallization water in gypsum! How is this possible? How does a plant get water from a mineral?

The actual physiological processes involved are not yet understood but there are some running hypotheses. The first has to do with temperature. When gypsum is exposed to temperatures above 40 degrees C, water can be released from the crystalline matrix. It would then be available to the plants via passive uptake. 40 degrees C is not unheard of in these environments. Any water that isn't taken up by the plants could be reincorporated back into gypsum when things cool down at night. Another possibility is that H. squamatum grows its roots into and around the gypsum. Using root exudates, it is possible that the plant is able to dissolve gypsum to some degree, thus unleashing the water within. This may rely on the microbial community associated with the roots. Until further research can be done on this, the jury is still out.

The most exciting aspect of this research is the doors it has now opened in our search for extraterrestrial life. Life as we know it depends on water. Our search for this molecule has us looking for planets in a sweet spot where water can be found in a liquid state. Knowing now that at least some life on our planet is able to obtain water from gypsum broadens the kinds of places we can look. Mars is chock full of gypsum. Just sayin'.

Photo Credit: José María Escolano (http://bit.ly/ZeSVzB)

Further Reading:

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140818/ncomms5660/full/ncomms5660.html

![Stevenson, Robert A., Dennis Evangelista, and Cindy V. Looy. "When conifers took flight: a biomechanical evaluation of an imperfect evolutionary takeoff." Paleobiology 41.2 (2015): 205-225. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1437657301019-XB4EC6SKTUVRMO77C7XN/image.jpg)

![Photo credit:J. L. DeVore [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1436965972190-UHK0SJ1NG6LJ23870IV2/image.jpg)