Happy New Year, partner :)

Photo by Daniel Jolivet licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Truth About Mistletoe

While perusing a local indie market this weekend I noticed that there was a stand selling mistletoe branches. It was odd to note that, for as ubiquitous of a symbol it is during this time of year, so few people realize what these plants are all about.

A reference to mistletoe could be any number of plants in the order Santalales. It is a large and rather varied grouping but the common thread throughout Santalales is parasitism on some level. Many species grow in the form of a shrub that grows epiphytically and taps into a host tree. While most still undergo photosynthesis, they also obtain nutriment using specialized structures that plug into the vascular tissue of their host. If infestations are intense enough, mistletoe can kill a tree.

However, don't let this fact leave you with any animosity toward mistletoe. Far from being a drain on the ecosystem, evidence is showing that many mistletoe species are keystone organisms where they are native. They produce copious amounts of berries that attract and feed a wide variety of birds and their growth habit makes for great nesting sites as well. Their leaves and shoots are munched on by a multitude of insect life, which then attracts animals higher up the food chain. Because of the preponderance of bird species that frequent mistletoe, other berry producing plants in the area benefit as well. In one study, researchers found that junipers had higher rates of reproduction when growing near mistletoe. Because mistletoe attracts all of those berry eating birds, numbers of seed carriers significantly increase for all other berry producing plants.

The most commonly encountered species of mistletoe is probably Viscum album. This evergreen species ranges from north Africa to southern England all the way to parts of Asia. It is evergreen and seems to really like growing on apple trees (Malus sp.). My favorite thing about this species as well as many other mistletoe is how they manage to reproduce. As mentioned above, they produce plump berries that birds can't resist. The pulp of the berry is quite sticky and thick that when the bird digests what it can and voids the rest, it has to wipe itself on a branch. This causes the mistletoe seed to stick to the branch like glue. When the seed germinates it attaches itself to the tree, living independently at first but later tapping into the trees vascular tissue. Next time you pucker up with someone special under one of these plants, keep that in the back of your mind!

Photo Credit: Martin LaBar

Further Reading:

http://www.kew.org/plants-fungi/Viscum-album.htm

http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114024

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2307/4013039/abstract

A North American Cycad and its Butterfly

Photo by andy_king50 licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Most of us here in North America probably know cycads mainly from those encountered in botanical gardens or as the occasional houseplant. However, if you want to see a cycad growing in the wild, you don't have to leave North America to do so. One must only travel to parts of Georgia and Florida where the coontie can be found growing in well drained sandy soils.

Known scientifically as Zamia integrifolia, the coontie is a cycad on a small scale. Plants are either male or female and both are needed for viable seed production. Here in the United States, the coontie is considered near threatened. Decades of habitat destruction and poaching have caused serious declines in wild populations. This has come at a great cost to at least one other organism as well.

Photo by James St. John licensed under CC BY 2.0

Thought to be extinct for over 20 years, a butterfly known as the atala (Eumaeus atala) require this lovely little cycad to complete their lifecycle. The coontie produces a toxin known as "cycasin" and, just as monarchs become rather distasteful to predators by feeding on milkweeds during their larval stage, so too do the larvae of the atala. The brightly contrasting colors of both the caterpillars and the adults let potential predators know that messing with them isn't going to be a pleasant experience. The reason for its decline in the wild is due to the loss of the coontie.

Rediscovered only recently, populations of this lovely butterfly are starting to rebound. Caterpillars of the atala are voracious eaters and a small group of them can quickly strip a coontie of its foliage. For this reason, large populations of coontie are needed to support a viable breeding population of the atala. The coontie is becoming a popular choice for landscaping, especially in suburban areas of southeastern Florida, which is good news for the atala. As more and more people plant coonties on their property, more and more caterpillars are finding food to eat. This just goes to show you the benefits of planting natives!

Photo by Neil Howard licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The Story of a Tree

I would like to tell you a story. A painfully oversimplified story, but a good one nonetheless. While this is my version of the story, it is by no means only mine. This is just another story of life on this planet and its relation to other living things. I hope you enjoy!

Our story starts with a tree. The tree is old and it is dying. This is okay. Throughout its long life the tree has produced millions of seeds and it is likely that at least a few of them are in the process of growing into new trees. It has replaced itself, the crowning achievement of all life on this planet. The tree has been through a lot during its time on Earth but now its life is coming to an end. You see, the tree has an infection. A fungal spore landed and began to grow on the scar of a branch that broke off during a wind storm.

The fungus is now spreading through the tissues of the tree. It started slowly at first but now it has reached critical mass. The fungus is consuming living tissues faster than the tree can repair them. It is a losing battle for the tree but a winning one for the fungus. As more and more of the tree dies, the dead wood becomes soft with yet more fungi. The softer the wood gets, the more appealing it becomes to insects. Beetles can sense the tree is dying and they swarm all over it, laying eggs under the bark. These eggs hatch into beetle grubs that live on wood. Ants soon find the tree as well. They are carpenter ants and these ants are young queens. One of the queens begins laying eggs and soon a whole colony of carpenter ants is living within the wood of the tree. As they eat their way through the wood more and more of the tree is dying.

Soon the last vestiges of life disappear from the tree. Spring comes and no buds break, no leaves grow, and no more water is pumped through its tissues. The story of the tree does not end here though. Far from it. All this insect activity has brought some new attention to the tree. Woodpeckers love insects and they begin to descend on the tree with vigor. Because woodpeckers are so territorial soon only a single pair visits the tree. At first it is simply to eat the myriad of insects living within the tree itself but, as their bond grows stronger, the pairs focus soon turns to producing offspring of their own.

Instead of chipping shallow feeding holes into the tree, the pair begin to excavate a nest hole. This hole is much deeper, extending into the middle of the tree. With copious amounts of insects and a few trees under their control, the pair of woodpeckers successfully raise many woodpecker offspring summer after summer. The tree served them well. In the winter, the nest hole served to shelter a flock of chickadees from the extreme cold. The chickadees don't know it but they owe their life to the woodpeckers for having excavated that hole. Winters are cold in this neck of the woods and without a place to gather together for warmth during the night, the little chickadees could have very well froze to death.

One summer the pair of woodpeckers do not return. Perhaps one of them flew into a car or got picked off by a cat. Either way, the nest hole was vacant one night when a flying squirrel found it. The squirrel was looking for a place to sleep during the day and the hole served her nicely. She stayed there all summer and into the winter. Like the chickadees, flying squirrels also congregate together in cavities during the winter for warmth. The hole suited them well. One of those squirrels happened to be a male that won her over come spring. Together they raised a small brood that year. Being fond of fungi, the flying squirrels were often covered in spores while feeding. These spores were brushed off in the hole whenever they returned home to their young.

These spores began to grow and, over the following seasons, the middle of the tree was nearly hollowed out. The tree stood for a few more seasons after this but finally, after years of insects and fungi eating it away, the tree collapsed. Again, this was not the end of the line for the tree. Soon the forest floor began to reclaim what was left. Fern spores landed on the waterlogged shell of the tree and there they germinated and grew. Moss spores did the same. In time a family of shrews made a den under the tree. Many a baby shrew was raised in this den.

One day a birch seed landed on the rotting bark. Here, far from competition on the forest floor, the seed germinated. The trees roots dug deep into the soggy tissues of the tree and soon found their way down into the dirt. Once in contact with the rich humus the trees growth took off. It rocketed into the canopy, vying for a place in the sun. Soon there was nothing left of the tree we started with. It rotted out from underneath the birch. Now, part of the humus itself, it went on to nourish the birch, which had become a full grown tree. One winter day a storm blew in. The storm brought with it a heavy load of snow. One of the birch's branches couldn't take the weight. With a loud snap that woke a sleeping owl, it crashed to the ground. The following spring a few fungal spores landed on the scar and started to grow into the birch.

Photo Credit: Neil Howard (http://bit.ly/1bJukbn)

Carnivores in Amber

Carnivorous leaves from Eocene Baltic amber. (A) Overview of the leaf enclosed in amber showing the adaxial tentacle-free side in slightly oblique view and stalked glands at the margin and on the abaxial side; arrowhead points to the exceptional long tentacle stalk with several branched oak trichomes attached. (B) Overview of the leaf enclosed in amber, showing abundant tentacles on the abaxial side. (C) Margin of abaxial leaf surface with tentacles of different size classes and nonglandular trichomes [SOURCE]

Carnivorous plants are marvels of evolution. Adapting to nutrient poor conditions, these botanical curiosities have evolved myriad ways of capturing and digesting prey. For all of their extant diversity, the fossil record of carnivorous plants over the eons is pretty much non existent save for some highly contentious fossils from China as well as some fossilized seeds of the aquatic carnivore, Aldrovanda. However, a recent discovery out of Russia changes everything. Beautifully preserved in amber, we now have the first conclusive fossil evidence of a carnivorous plant.

The amber was found in a mine in Russia and is estimated to be between 35 and 47 million years old, during an epoch known as the Eocene. Inside are beautifully preserved leaves of what seems to be a species of Roridula. The leaves clearly show specialized stalked glands with a pore at the tip. The researchers who discovered the amber also found evidence of the sticky secretions that were used to capture its prey.

Overviews showing the tentacle-free adaxial surface and tentacles along the leaf margins (B & C). (D) Partial leaf tip showing different size classes of stalked glands. [SOURCE]

The resemblance of these leaves to the leaves of extant Roridula is uncanny. Modern Roridula do not directly digest their prey. Instead, they rely on a symbiotic relationship between a species of bug, which lives on the leaves without getting stuck. The bugs hunt down and eat trapped insects. As they eat, the bugs defecate and it is their nitrogen-rich feces that the plants absorb for sustenance. It is quite possible that the fossilized Roridula also relied on these insects as well, though no direct evidence of this was found.

The most interesting aspect of this discovery is its location. Today, Roridula is found only in South Africa. Its presence in Russia hints at a historic distribution that is much wider than previously thought. It has long been assumed that Roridula is a neoendemic to South Africa, with the family having arisen there and nowhere else. This discovery now shows Roridula to be a paleoendemic, once having a much wider distribution but currently restricted to South Africa. This discovery is an excitingly huge step in our understanding of carnivorous plant evolution.

Morphological comparison of the carnivorous leaf fossils from Baltic amber (Left) and extant Roridula species (Right). (A and B) Leaf tip ending in a sole tentacle. (C and D) Stalked glands of different size classes. (E and F) Hyaline unicellular nonglandular trichomes. (G and H) Epidermal cells and stomata. (I–L) Multicellulartentacles. (A, C, E, and G) (I and J). (B, D, K, and L) R. gorgonias. [SOURCE]

Photo Credit: Alexander R. Schmidt, University of Göttingen

Further Reading: [1]

I've Got the Colorado Blues

Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service (retired), Bugwood.org licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

You would be hard pressed to find a resident of temperate North America who has never seen a Colorado blue spruce. These iconic trees are a staple of every sapling give-away and can be found in countless landscape plans all over the continent. There is no denying the fact that the blue hues of Picea pungens have managed to tap into the human psyche and in doing so has managed to spread far beyond its relatively limited range. However, despite its popularity, few people ever really get to know this species. Even fewer will ever encounter it in the wild. Today I would like to introduce you to a brief natural history of Picea pungens.

Despite its common name, P. pungens is not solely a denizen of Colorado. It can be found in narrow swaths of the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, Idaho, south to Utah, northern and eastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, and of course, central Colorado. There are also some rumored populations in Montana as well. It has a very narrow range compared to its more common relative, the Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii). Whereas some authors consider the Colorado blue spruce to be a subspecies of the Engelmann spruce, the paucity of natural hybrids where these two species overlap suggests otherwise. It is likely that Colorado blue spruce split off from this lineage at some point in the past and has been following its own evolutionary trajectory ever since.

Female cones are quite attractive when they emerge. Photo by JJ Harrison (https://www.jjharrison.com.au) licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

One of the reasons P. pungens has become such a popular landscape tree is due to its extreme hardiness. Indeed, this is one sturdy tree species. Not only can it handle drought, P. pungens is also capable of surviving temperatures as low as -40 degrees Celsius with minimal foliar damage. Little stands in the way of a well established Colorado blue. In the wild it can be found growing on gentle mountain slopes at elevations of 6,000 to 10,000 feet (1,800 to 3000 m). It is also a long lived and highly fecund tree. The most highly productive seed years for P. pungens begin at age 50 and last until it reaches roughly 150 years of age. Seeds germinate best on bare soils, which probably keeps this species limited to these mountainous areas in the wild.

The typical female cone of the Colorado blue spruce. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Public Domain

Another component of its landscape popularity is its characteristic blue color. In reality, not all trees exhibit this coloration. Its blue hue is the result of epicuticular wax deposits on the leaves as they are produced in the spring. Individual trees rpduce varying amounts and consistencies of wax and therefore may not appear blue. Wax production seems to be controlled by a genetic factor and therefore is often a shared trait among isolated populations. The wax functions as sun screen, reflecting harmful UV rays away from sensitive developing foliage. This is why it is most prominent in new growth. The wax can and often does degrade over the span of a growing season, resulting in duller trees come fall.

Despite how interesting this spruce is, Picea pungens, in my opinion, represents the epitome of lazy landscaping. Like Norway spruce (Picea abies) and Norway maples (Acer platanoides), P. pungens seems to be an all-too-easy choice for those looking to save a quick buck. As a result, countless numbers of these trees line streets and demarcate property boundaries. Though P. pungens is native to North America, its narrow home range makes its ecological function elsewhere quite minimal. Sure, one could certainly do worse than planting this conifer, but it nonetheless overshadows more ecologically friendly tree choices. If you are looking to add a new tree to your landscape, take a few minutes to search for more ecologically friendly species that are native to your region.

Photo Credit: [1] [2] [3]

Further Reading: [1] [2] [3] [4]

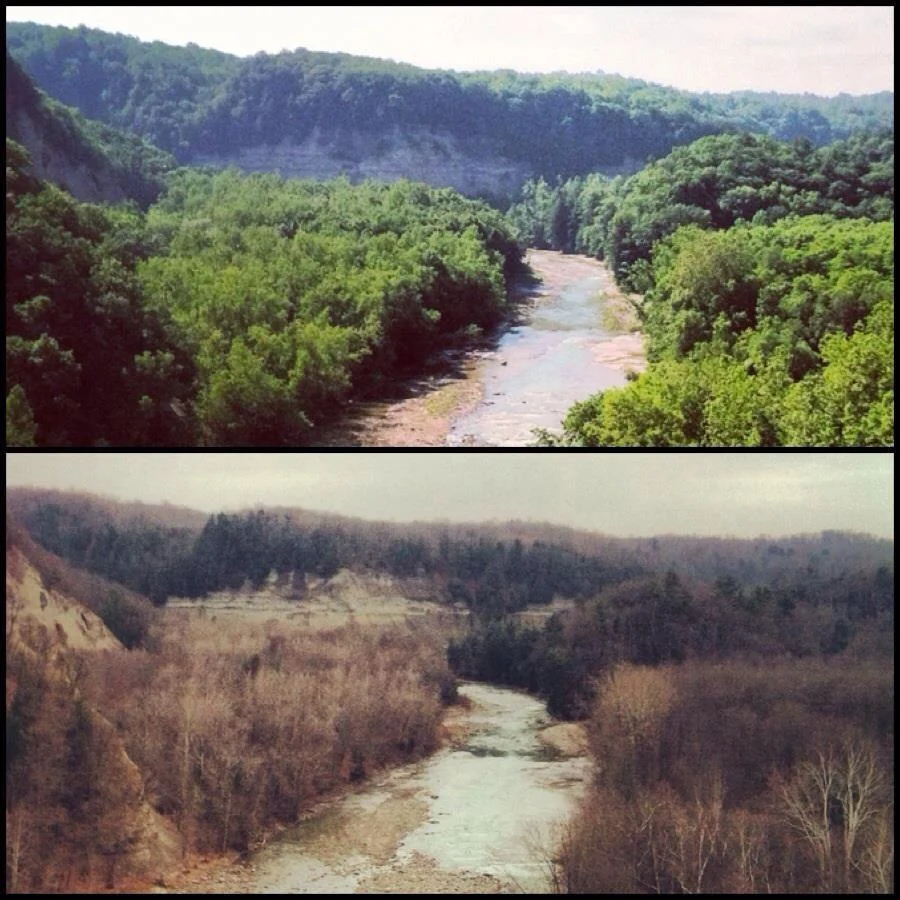

Time

I love temporal changes in the landscape. I appreciate that technology allows me to visualize some of my favorite hiking places from many different angles.

![Overviews showing the tentacle-free adaxial surface and tentacles along the leaf margins (B & C). (D) Partial leaf tip showing different size classes of stalked glands. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1574712995157-PDQXZKTLFXOY7MEJ3YGJ/camb3.JPG)