When the move to Illinois was finalized I set a goal for this spring. It is always good to have goals and mine was to see a large population of shooting stars. I am, of course, not talking about the ones from outer space but rather plants of the genus Dodecatheon. Various nature centers in this region boast lovely photos of hillsides covered in them. Except for my time in Wyoming where Dodecatheon conjugens often kept me preoccupied on hikes, I have only seen Dodecatheon as a spattering of individuals. This past weekend I met my goal.

We were hiking up a wooded hillside when I noticed a few rosettes of fleshy, light green leaves. This is where having a search image comes in handy. There was no mistaking these plants. At first it seemed as if we were meeting a bit too early. I could just make out some flower buds poking up from the middle of the rosette. However, further up on the ridge, a warmer microclimate rewarded us with quite the display. All along the sun-streaked hillside were hundreds of shooting stars just starting to bloom. What's more, these were a unique species of shooting star I had never seen before.

Dodecatheon frenchii is as Midwestern as it gets for this genus. This particular species is known from only six states. It prefers to grow in shallow sandy soils along the southern edge of the glacial boundary. Often times it can be found at the base of sandstone cliffs and ledges. Taxonomically speaking, this species is quite interesting. It is very similar to D. meadia. In fact, some authors lump them together. The greatest difference between these plants, however, lies in their chromosomes as well as their habitat preferences. D. frenchii is diploid and is a sandstone endemic, whereas D. meadia is tetraploid and much more widespread.

Despite their limited range, D. frenchii are quite hardy. Growing in sandy soil has its challenges. The biggest issue plants face is drought. When summer really heats up, these plants go dormant. Their thick roots store water and nutrients to fuel their growth the following year. Due to the nature of their preferred habitat, few other plants can be found growing with D. frenchii. That's not to say nothing can, however, competition is minimal. As such, D. frenchii does not compete well with other plants, which certainly sets limits on its preferred habitat. Like all members of this genus, D. frenchii flowers are adapted for buzz pollination. Certain bees, when landing on the downward pointing stamens, vibrate their bodies at a special frequency that causes pollen to be released.

Seeing these plants in person lived up to all of the hype. It was one of those botanizing moments I will never forget. Although I often go outside with the simple goal of just being in nature, sometimes having a specific mindset makes for a fun adventure. If anything, it makes for some great bonfire stories. So here's to spring and to Dodecatheon and to just getting outside.

Further Reading:

http://bit.ly/1U69kj1

http://bit.ly/1rht7Bl

Lovely Lomatium

I officially learned how to botanize in the American west. Before then my skills were limited to "hey, look at the pretty flower" and then Googling my way to an answer. As such, I have a real soft spot for western botany. Despite the fact that I have not had the chance to exercise those muscles in some time, I nonetheless revisit the few groups that I do remember via the massive photo collection I built up during my tenure in Wyoming. One group I am particularly fond of are members of the genus Lomatium.

I had never really paid attention to members of the carrot family. I always associated that group with the Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota) I encountered growing in ditches. In other words, I found them boring. All of that changed when I moved to Wyoming. Spring was slow to start that year. I mean really slow. I thought I had it bad in western New York where spring snow storms and freezing temperatures often delayed plant growth well into May. That year in Wyoming, the last snow storm hit on June 29th. Because of this, most of the plants we were trying to locate were biding their time underground waiting for favorable weather to kick off the growing season.

By mid June I was starving for plant life. I needed to see some greenery. That is when I first laid eyes on a Lomatium. They began appearing as tight clusters of highly dissected, rubbery leaves. Once I knew what to look for, I began finding them throughout the foothill regions where we were working. Since I was just getting familiar with the local flora, I was hard pressed to key anything out. Instead I just waited for flowers. I didn't have to wait very long.

Soon entire hillsides were covered in little yellow umbels. They were squat plants, never growing too high. The constant winds that whipped across the terrain made sure of that. It soon became apparent that Lomatiums don't waste any time. Water is limited in these habitats and they have to make quick work of it while it is available. Another interesting thing to note is the sex of the flowers. Generally when I see a dense umbel like that, I just assumed they were hermaphroditic. In at least some Lomatium, this is actually not the case. The sex of the flowers is determined by age.

Smaller plants tend to produce male flowers, whereas larger plants will produce hermaphrodites. This makes a lot of sense as producing only pollen requires much fewer resources than producing ovaries and eventually seeds. Needless to say, larger plants also produce the most seed and are often the driving force in population persistence and growth. The seeds themselves are quite interesting. They are winged and often quite fleshy until they dry. Wind is the predominant seed dispersal mechanism and there is no shortage of wind in sagebrush country.

The phylogeny of this genus is quite confusing. I certainly haven't gotten my head wrapped around it. Individuals are notoriously hard to identify both physically and genetically. There is a large degree of genetic variation between plants and "new species" are still being discovered. At the same time, there is also a lot of endemism and some species like Lomatium cookii and Lomatium dissectum are of conservation concern. Aside from habitat destruction, over-grazing, and limited ranges, over-collection for herbal uses poses considerable threat to many species.

Further Reading:

Meeting Blue-Eyed Mary

For some plant species, pictures will never do them justice. I realized this when I first laid eyes on a colony of blue-eyed Mary (Collinsia verna). I was smitten. These lovely little plants lined the trail of a floodplain forest here in central Illinois. It was the blue labellum that first caught my eye. After years of reading about and seeing pictures of these plants, meeting them in person was a real treat.

C. verna is winter annual meaning its seeds germinate in the fall. The seedlings lie dormant under the leaf litter until spring warms enough for them to start growing. Growth is rapid. It doesn't take long for them to unfurl their first flowers. And wow, what flowers they have!

The bicolored blooms are a real show stopper. The lower lip contrasts starkly with the white top. It's about as close to true blue as a flower can get. Not only are they beautiful, the flowers are marvels of evolution, exquisitely primed for pollination by large, spring-hardy insects. When something the size of a bumble bee lands on the flower, the lower lip parts down the middle, thrusting the reproductive bits up against the abdomen. This plant doesn't take any chances.

Being an annual, C. verna can only persist via its seed bank. Populations can be eruptive, often appearing in mass after a disturbance clears the forest of competition. Most populations exist from year to year as much smaller patches that slowly build the seed bank in preparation for more favorable conditions in the future. Because of its annual life cycle, C. verna can be rather sensitive to habitat destruction.

Seeing this plant with my own eyes far exceeded my expectations. It was one of those moments that I couldn't peel myself away from. I love spring ephemerals and this species has skyrocketed to the top of my list. Its beauty is made all the more wonderful by its ephemeral nature. Enjoy them while they last as it may be some time before you see them again.

Further Reading: [1] [2] [3]

Sand Armor

Photo by Franco Folini licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Plants go through a lot to protect themselves from the hungry jaws of herbivores. They have evolved a multitude of ways in which to do this - toxins, stinging hairs, thorns, and even camouflage. And now, thanks to research by a team from UC Davis, we can add sand to this list.

At this point you may be asking "sand?!" Stick with me here. Undoubtedly you have noticed that sticky plants often have bits of whatever substrate they are growing in stuck to their stems and leaves. You wouldn't be the first to notice this. Back in 1996 a term was coined for this very phenomenon. It has been called “psammophory,” which translates to "sand-carrying."

Over 200 species of plants hailing from 88 genera in 34 families have been identified as psammorphorous. The nature of this habit has been an object of inquiry for at least a handful of researchers over the last few decades. Hypotheses have ranged from protection from physical abrasion, reduction of water loss, reduced surface temperature, reduced solar radiation, and protection from herbivory.

It was this last hypothesis that seemed to stick. Indeed, many plants produce crystalline structures in their tissues (phytoliths, raphides, etc., which are often silica or calcium based) to deter herbivores. Sand, being silica based, is known to cause tooth wear in humans, ungulates, and rodents. Perhaps a coating of sand is enough to drive away insects and other hungry critters looking to snack on a plant.

By controlling the amount and color of the sand stuck to plants, the researchers were able to demonstrate that plants covered in sand were less palatable to both mammalian and insect herbivores. In total, sand-covered individuals received significantly less damage to their leaves than individuals that had their sand coat removed. By altering the color of the sand, the researchers were able to demonstrate that this was not a function of camouflage. In total, the presence of sand led to an overall increase in fitness due to a decrease in damage over time. These results are the first conclusive evidence in support of psammophory as yet another fantastic plant defense mechanism.

Photo Credit: Franco Folini (bit.ly/1RApG1R) and Wolfram Burner (http://bit.ly/1RMNR9V)

Further Reading:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1890/15-1696/abstract

Photo by Wolfram Burner licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The Fall of Corncockle

Photo by Sonnentau licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

This switch from more traditional farming practices to industrialized monocultures has left a damaging legacy on ecosystems around the globe. This is especially true for unwanted plants. Species that once grew in profusion are now sprayed and tilled out of existence. Nowhere has this been better illustrated than for a lovely little plant known commonly as the corncockle (Agrostemma githago).

This species was once a common weed in European wheat fields. Throughout much of the 19th and early 20th century, it was likely that most wheat sold contained a measurable level of corncockle seed. Its pink flowers would have juxtaposed heavily against the amber hue of grain. Indeed, its habit of associating with wheat has lead to its introduction around the globe. It can now be found growing throughout parts of North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

However, in its home range of Europe, the corncockle isn't doing so well. The industrialization of farming dealt a huge blow to corncockle ecology. The broad-scale application of herbicides wreaked havoc on corncockle populations. Much more detrimental was the switch to winter wheat, which caused a decoupling between harvest time and seed set for the corncockle. Whereas it once synced quite nicely with regular wheat harvest, winter wheat is harvested before corncockle can set seed. As such, corncockle has become extremely rare throughout its native range and was even thought to be extinct in the UK.

A discovery in 2014 changed all of that. National Trust assistant ranger Dougie Holden found a single plant flowering near a lighthouse. Extensive use of field guides and keys confirmed that this plant was indeed a corncockle, the first seen blooming in the UK in many decades. It is likely that the sole plant grew from seed churned up by vehicle traffic the season before.

Photo Credit: sonnentau (bit.ly/1qo3XQK)

Further Reading:

Clapham, A.R., Tutin, T.G. and Warburg, E.F. 1968. Excursion Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press

The Dune Building Powers of Sand Cherry

Throughout a surprising amount of North America, dunes and other highly erosional habitats have a friend in the sand cherry (Prunus pumila). I first met this cherry on the shores of Lake Huron where it blankets dunes with its scrambling, prostrate branches.

Sand cherry can be found growing in dry, sandy areas. Its ability to grow in such places makes it an important soil stabilizer and dune builder. It sends down a deep root system that anchors sand in place. As the dune system grows, it sends out more and more branches, further stabilizing these relatively unstable habitats. This also begins the process of soil formation. By stabilizing the sandy dune soils, sand cherry enables other plants to take root. This in turn leads to the colonization of microbes and invertebrates that begin breaking down biological materials, thus forming the foundation of organic soil.

Photo by Joshua Mayer licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Mature sand cherries begin blooming in April and will continue doing so into June in cooler climates. The flowers are followed by small cherries that are relished by a variety of animals. Aside from food, its thick growth habit also provides ample shelter and breeding opportunities for a insects, birds, and mammals alike.

Taken together, sand cherry is quite the ecosystem engineer. Because of its drought tolerance, sand cherry is also gaining some popularity among habitat restoration practitioners as well as anyone looking for hardy yet beautiful landscape specimen. Individuals growing on more stable, less wind-swept ground will take on a more upright appearance. All in all this may be one of my favorite members of the genus Prunus.

Photo Credit: Joshua Mayer (http://tinyurl.com/znrh8e2)

Further Reading: [1]

Pasqueflower

Photo by Jerzy Strzelecki licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The true harbinger of spring on the northern prairies of North America, Europe, China and Russia is none other than the pasqueflower (Anemone patens). It bursts forth from the ground with its fuzzy, dissected leaves often before all of the snow has had a chance to melt. It then proceeds to put on quite a show with flowers that range the spectrum from white to deep purple. Everything about this plant is adapted to take advantage of early spring before competing vegetation gets the upper hand.

One of the coolest aspects of pasqueflower life are its flowers. These parabolic beauties need to be able to function despite the constant risk of freezing temperatures. To stay warm, the flowers will actually track the sun's movement across the sky. In this way, they are able to absorb solar radiation all day. What's more, the parabolic shape and reflective surface of the petals serves to bounce solar radiation towards the center, thus amplifying the amount of heat. Pasqueflower blooms can actually maintain a daytime flower temperature upwards of 18 degrees Celsius above ambient temperatures, not only providing a warm spot for pollinators but also increasing the rate at which the seeds develop.

Photo by Otro13 licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The seeds themselves are quite interesting structures as well. Getting into the soil can be a difficult task when your neighbors are thick prairie grasses. Pasqueflowers get around this problem by producing seeds that literally bury themselves. Each seed is attached to an awn that is made up of alternating strands of tissue. Each strand varies in its ability to absorb moisture. As spring rains come and go, the awns will twist and turn with the resulting effect of drilling the seeds directly into the ground.

Once the surrounding vegetation begins to wake up, pasqueflower is already getting ready to go dormant. By mid-July it is usually back underground. It is a prime example of how breaking dormancy early can help a plant beat the competition of the growing season. Also, pasqueflower can be very long lived, with individuals persisting upwards of 50 years in a given location. Not only is this plant is both hardy and beautiful, it also has the added ecological benefit of providing early prairie pollinators with a much needed boost of energy.

Photo Credit: [1] [2]

Further Reading: [1] [2]

Of Gunnera and Cyanobacteria

Photo by UnconventionalEmma licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Nitrogen is a limiting resource for plants. It is essential for life functions and yet they do not produce it on their own. Instead, plants need to get it from their environment. They cannot uptake gaseous nitrogen, which is a shame because it makes up 78.09% of our atmosphere. As such, some plants have developed very interesting ways of obtaining nitrogen from their environment. Some, like the legumes, produce special nodules on their roots, which house bacteria that fix atmospheric nitrogen. Other plants utilize certain species of mycorrhizal fungi. One family of plants, however, has evolved a symbiotic relationship that is unlike any other in the angiosperm world.

A Gunnera inflorescence. Photo by Lotus Johnson licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Meet the Gunneras. This genus has a family all to itself - Gunneraceae. They can be found in many tropical regions from South America to Africa and New Zealand. Some species of Gunnera are small while others, like Gunnera manicata, have leaves that can be upwards of 6 feet in diameter. Their leaves are well armed with spikes and spines. All in all they are rather prehistoric looking. The real interesting thing about the Gunneras though, is in the symbiotic relationship they have formed with cyanobacteria in the genus Nostoc.

Traverse section of a Gunnera stem showing cyanobacteria colonies (C) and the cup-like structures (S) where they enter the stem. [SOURCE]

Gunnera produce cuo-like glands that house these cyanobacteria. The glands are filled with a special mucilage that not only attracts the cyanobacteria, but also stimulates it to grow. Once inside the glands, the cyanobacteria begins to grow into the plant, eventually fusing with the Gunnera cells. From there the cyanobacteria earn their keep by producing copious amounts of usable nitrogen and in return, the Gunnera supplies carbohydrates. This relationship is amazing and quite complex. It also offers researchers an insight into how such symbiotic relationships evolve.

Velvet Turtleback

Photo by Stan Shebs licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Death valley doesn't seem like a place where life would thrive. Nonetheless, a unique assemblage of plants can be found living in this hostile environment. These plants are well adapted to take advantage of those fleeting moments when things aren't so bad. A flush of flowers following a rare desert downpour is a reminder that even the harshest environments on this planet can harbor rich biodiversity. One of the coolest plants found in Death valley has to be the velvet turtleback (Psathyrotes ramosissima).

This peculiar little aster forms fuzzy little cushions that superficially resemble the domed shell of a turtle. The tightly packed leaves even give the appearance of scales. Everything about this plant is adapted to life in one of the driest places on Earth. For starters, it is a desert annual. Its seeds can lie dormant in the soil for many years until the perfect conditions arise. Once that happens, growth can be surprisingly rapid. In Death Valley, good conditions don't last long.

Photo by Dawn Endico from Menlo Park, California - Turtleback Uploaded by PDTillman licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Even when conditions are right, its desert environment can still be quite challenging. Water loss and sun scorch are constant threats. Its cushion-like growth form and fuzzy leaves help reduce water loss as hot, dry winds whip across the region. The fuzzy leaves also help to reflect punishing UV rays that may otherwise fry the sensitive photosynthetic machinery inside.

All in all this is an incredible little plant. It survives in one of the toughest environments on the planet through a combination of timing and physiology. It is also but one of many desert-adapted species painting the valley during the brief growing season. As is typical of most of the plants of this region, its beauty is ephemeral and won't last much longer and to me, that makes it all the more wonderful.

Photo Credits: Stan Shebs and Dawn Endico - Wikimedia Commons

An Underground Orchid

Photo by Jean and Fred licensed under CC BY 2.0

Are you ready to have your mind blown away? What you are looking at here is not some strange kind of mushroom, though fungus is involved. What you are seeing is actually the inflorescence of a parasitic orchid from Australia that lives and blooms underground!

Meet Rhizanthella gardneri. This strange little orchid is endemic to Western Australia and it lives, blooms, and sets seed entirely underground. It is extremely rare, with only 6 known populations. Fewer than 50 mature plants are known to exist. This is another one of those tricky orchids that does not photosynthesize but, instead, parasitizes a fungus that is mycorrhizal with the broom honey myrtle (Melaleuca uncinata). To date, the orchid has only been found under that specific species of shrub. Because of its incredibly unique requirements, its limited range, and habitat destruction, R. gardneri is critically endangered.

The flowers open up a few centimeters under the soil. They are quite fragrant and it is believed that ants, termites, and beetles are the main pollinators. The resulting seeds take up to 6 months to mature and are quite fleshy. It is hypothesized that some sort of small marsupial eats them and consequently distributes them in its droppings. Either way, the chances of successful sexual reproduction for this species are quite low. Because of this, R. gardneri also reproduces asexually by budding off daughter plants.

Despite not photosynthesizing, this orchid is quite unique in that it still retains chloroplasts in its cells. They are a very stripped down form of chloroplast though, containing about half of the genes a normal chloroplast would. It is the smallest known chloroplast genome on the planet. This offers researchers a unique opportunity to look deeper into how these intracellular relationships function. The remaining chloroplast genes code for 4 essential plant proteins, meaning chloroplasts offer functions beyond just photosynthesis.

I am so amazed by this species. I'm having a hard time keeping my jaw off the ground. What an amazing world we live in. If you would like to see more pictures of R. gardneri, please make sure to check out the following website:

http://www.arkive.org/underground-orchid/rhizanthella-gardneri/

Photo Credit: Jean and Fred Hort

Further Reading:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/02/110208101337.htm

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-02/uowa-wai020711.php

http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=20109

Studying Mimicry in Orchids Using 3D Printing

Photo by Luis Baquero licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Just when I thought I could stop acting surprised by the myriad applications of 3D printing, a recent study published in the journal New Phytologist has me pulling my jaw up off the floor. Using a 3D printer, researchers from the University of Oregon have unlocked the mystery surrounding one of the more peculiar forms of mimicry in the botanical world.

The genus Dracula is probably most famous for containing the monkey face orchids (Dracula simia). Thanks to our predisposition for pareidolia, we look at these flowers and see a simian face staring back at us. Less obvious, however, is the intricate detail of the labellum, which superficially resembles the monkey's mouth. A close inspection of this highly modified petal would reveal a striking resemblance to some sort of gilled mushroom.

Indeed, a mushroom is exactly what the Dracula orchids are actually trying to mimic. The main pollinators of this genus are tiny fruit flies that are mushroom specialists. They can be seen in the wild crawling all over Dracula flowers looking for a fungal meal and a place to mate. Some of the flies inevitably come away from the Dracula flower with a wad of pollen stuck to their backs. With any luck they will fall for the ruse of another Dracula flower and thus pollination is achieved.

Despite being well aware of this mimicry, scientists didn't quite know what specifically attracted the flies to the flower. This is where the 3D printer came in. The research team made exact replicas of the flowers of Dracula lafleurii out of odorless silicone. They also printed individual flower parts. In doing so, the researchers were able to vary the color patterns as well as the scent of each flower. Using the parts, they were also able to construct chimeras, which allowed them disentangle which parts contribute most to the mimicry.

What they discovered is that the key to Dracula's mushroom mimicry lies in its gilled labellum. This petal not only looks like a mushroom, it smells like one too. The result is a rather ingenious ruse that its tiny fly pollinators simply can't resist. What's more, this approach offers an ingenious way of investigating the evolution of mimicry throughout the botanical kingdom.

Photo Credit: Luis Baquero (http://bit.ly/21GhYGJ)

Further Reading:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nph.13855/abstract

Plant Plasticity

One of the central tenets of evolutionary science is that individuals within a species vary, however slightly, in their form, physiology, and behavior. Without variability, life would languish, remaining static in a soupy ooze somewhere in the oceans. Perhaps it may not have evolved in the first place. Regardless, observation and experimentation has taught us a lot about how variation among individuals or populations can drive evolution. Today I would like to introduce you to a tiny plant native to northern and western North America that is teaching us a lot about how mating systems develop in plants.

Meet Collinsia parviflora, the maiden blue eyed Mary. Few plants are as iconic to my time living out west than this wonderful little plant. Indeed, C. parviflora is highly variable. It ranges in size from 5 for 40 centimeters in height and produces lovely little flowers that range from 4 to 7 millimeters in length. The size range of these flowers is key to investigating variations in pollination strategies.

C. parviflora has evolved what researchers refer to as a mixed mating strategy. Populations differ in that some plants self pollinate whereas others fully outcross with the help of a variety of bees. Exactly why these plants would maintain both strategies can tell us a lot about how mating systems develop in plants. What researchers have found is that there seems to be a tradeoff.

Populations that frequently self are often located in the harshest environments. Cold temperatures and a short growing season make investing in complex floral development a risky strategy. Indeed, plants growing where environmental conditions are harshest produce smaller flowers. These small flowers pack all of their reproductive bits close together, thus increasing the chances of self fertilization. It has been found that despite the risk of inbreeding, these plants produce far more seeds than plants that produce larger flowers and experience high rates of insect pollination.

The reasons for this are quite complex and more work is needed to be certain but it would seem that this is all an evolutionary adaptation to dealing with varied climates. With wide ranging species like C. parviflora, populations can experience highly varied environmental conditions. It would seem maladaptive to focus in on one particular reproductive strategy. As such, C. parviflora has evolved a range of possible anatomies as a way of adapting to many unique local conditions. If times are good and pollinators are abundant, it makes more sense to hedge bets on sexual reproduction whereas when conditions are poor and pollinators are scarce, it makes sense to produce offspring with a genome identical to that of the parents. If they can exist in a harsh location then so can the cloned offspring.

Investigations into the mating system of this tiny plant has revealed that big things can really come in small packages. I miss seeing this species. Its amazing how these tiny little flowers can be so numerous as to turn wide swaths of its habitat a pleasing shade of blue.

Further Reading:

http://www.amjbot.org/content/90/6/888.full

http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=COPA3

Rhizanthes lowii

Photo Credit: Ch'ien C. Lee - www.wildborneo.com.my/photo.php?f=cld1500900.jpg

Imagine hiking through the forests of Borneo and coming across this strange object. It's hairy, it's fleshy, and it smells awful. With no vegetative bits lying around, you may jump to the conclusion that this was some sort of fungus. You would be wrong. What you are looking at is the flower of a strange parasitic plant known as Rhizanthes lowii.

Rhizanthes lowii is a holoparasite. It produces no photosynthetic tissues whatsoever. In fact, aside from its bizarre flowers, its doesn't produce anything that would readily characterize it as a plant. In lieu of stems, leaves, and roots, this species lives as a network of mycelium-like cells inside the roots of their vine hosts. Only when it comes time to flower will you ever encounter this species (or any of its relatives for that matter).

The flowers are interesting structures. Their sole function, of course, is to attract their pollinators, which in this case are carrion flies. As one would imagine, the flowers add to their already meaty appearance a smell that has been likened to that of a rotting corpse. Even more peculiar, however, is the fact that these flowers produce their own heat. Using a unique metabolic pathway, the flower temperature can rise as much as 7 degrees above ambient. Even more strange is the fact that the flowers seem to be able to regulate this temperature. Instead of a dramatic spike followed by a gradual decrease in temperature, the flowers of R. lowii are able to maintain this temperature gradient throughout the flowering period.

Photo Credit: Ch'ien C. Lee - www.wildborneo.com.my/photo.php?f=cld1500900.jpg

There could be many reasons for doing this. Heat could enhance the rate of floral development. This is a likely possibility as temperature increases have been recorded during bud development. It could also be used as a way of enticing pollinators, which can use the flower to warm up. This seems unlikely given its tropical habitat. Another possibility is that it helps disperse its odor by volatilizing the smelly compounds. In a similar vein, it may improve the carrion mimicry. Certainly this may play a role, however, flies don't seem to have an issue finding carrion that has cooled to ambient temperature. Finally, it has also been suggested that the heat may improve fertilization rates. This also seems quite likely as thermoregulation has been shown to continue after the flowers have withered away.

Regardless of its true purpose, the combination of lifestyle, appearance, and heat producing properties of this species makes for a bizarrely spectacular floral encounter. To see this plant in the wild would be a truly special event.

Photo Credit: Ch'ien C. Lee - www.wildborneo.com.my/photo.php?f=cld1500900.jpg

A Litter Trapping Orchid From Borneo

Ch'ien C. Lee - http://www.wildborneo.com.my/

Epiphytes live a unique lifestyle that can be quite challenging. Sure, they have a relatively sturdy place on a limb or a trunk, however, blistering sun, intense heat, and plenty of wind can create hostile conditions for life. One of the hardest things to come by in the canopy is a steady source of nutrients. Whereas plants growing in the ground have soil, epiphytes must make do with whatever falls their way. Some plants have evolve a morphology that traps falling litter. There are seemingly endless litter trapping plants out there but today I want to highlight one in particular.

Meet Bulbophyllum beccarii. This beautiful orchid is endemic to lowland areas of Sarawak, Borneo. What is most interesting about this species is how it grows. Instead of forming a clump of pseudobulbs on a branch or trunk, this orchid grows upwards, wrapping around the trunk like a leafy green snake. At regular intervals it produces tiny egg-shapes pseudobulbs which give rise to rather large, cup-shaped leaves. These leaves are the secret to this orchids success.

The cup-like appearance of the leaves is indeed functional. Each one acts like, well, a cup. As leaves and other debris fall from the canopy above, the orchid is able to capture them. Over time, a community of fungi and microbes decompose the debris, turning it into a nutrient-rich humus. Instead of having to compete for soil nutrients like terrestrial species, this orchid makes its own soil buffet!

If that wasn't strange enough, the flowers of this species are another story entirely. Every so often when conditions are just right, the plant produces an inflorescence packed full of hundreds of tiny flowers. The flowers dangle down below the leaves and emit an odor that has been compared to that of rotting fish. Though certainly disdainful to our sensibilities, it is not us this plant is trying to attract. Carrion flies are the main pollinators of this orchid and the scent coupled with their carrion-like crimson color attracts them in swarms.

The flies are looking for food and a place to lay their eggs. This is all a ruse, of course. Instead, they end up visiting a flower with no rewards whatsoever. Regardless, some of these flies will end up picking up and dropping off pollinia, thus helping this orchid achieve pollination.

Epiphyte diversity is incredible and makes up a sizable chunk of overall biodiversity in tropical forests. The myriad ways that epiphytic plants have adapted to life in the canopy is staggering. Bulbophyllum beccarii is but one player in this fascinating niche.

Photo Credits:

Ch'ien C. Lee - http://www.wildborneo.com.my/

Further Reading:

http://www.orchidspecies.com/bulbbeccarrii.htm

Bowerbirds - Accidental Gardeners

To look upon the bower of a male bowerbird is to see something bizarrely familiar. These are not elaborate nests but rather architectural monuments whose sole purpose is to serve as a staging ground for mating displays. Males build and adorn these structures with precision and a sense of aesthetics. Because of this behavior, at least one species of bowerbird, the spotted bowerbird, can add another occupation to its resume - accidental gardener.

When a male finds a certain color he likes, he scours the landscape in search of these treasures. For many male bowerbirds, fruits offer a wide array of colors and textures of which they can add to their menagerie. Male spotted bowerbirds seem to have a fondness for the fruits of the potato bush (Solanum ellipticum). Their stark green hue contrasts nicely with the bower architecture.

When the fruits start to decompose, they no longer serve any purpose for the male bowerbird and he tosses them aside. Seeds begin to accumulate around the bower and after some time they will germinate. Researchers decided to investigate this relationship a bit further. What they found was pretty astounding.

They discovered that bush potato plants grew in higher numbers around bowers than they do at random locations throughout the forest. What's more, the fruits produced by bush potatoes growing near bowers were much greener than those of plants elsewhere. In effect, male spotted bowerbirds are not only cultivating the bush potato, they are also artificially selecting for improved coloration of its fruits.

To date, this is the only example of something other than a human cultivating a plant for reasons other than food. The similarities between human cultivation and bowerbird cultivation are mind blowing. Similar to human farmers, male bowerbirds clear the site of competing vegetation and remove the fuel load so as to minimize the risk of fire, all of which provides ideal habitat for germination. Though the male bowerbirds are not intentionally cultivating the bush potato, they have nonetheless entered into a mutualistic relationship in which the males get ready access to beautiful fruits and in return, the bush potato gets a nice, safe place to grow.

Photo Credit: University of Exeter

Further Reading:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982212002084

Hyperabundant Deer Populations Are Reducing Forest Diversity

Synthesizing the effects of white-tailed deer on the landscape have, until now, been difficult. Although strong sentiments are there, there really hasn't been a collective review that indicates if overabundant white-tailed deer populations are having a net impact on the ecosystem. A recent meta-analysis published in the Annals of Botany: Plant Science Research aimed to change that. What they have found is that the overabundance of deer is having strong negative impacts on forest understory plant communities in North America.

White-tailed deer have become a pervasive issue on this continent. With an estimated population of well over 30 million individuals, deer have been managed so well that they have reached proportions never seen on this continent in the past. The effects of this hyper abundance are felt all across the landscape. As anyone who gardens will tell you, deer are voracious eaters.

Tackling this issue isn't easy. Raising questions about proper management in the face of an ecological disaster that we have created can really put a divide in the room. Even some of you may be experiencing an uptick in your blood pressure simply by reading this. Feelings aside, the fact of the matter is overabundant deer are causing a decline in forest diversity. This is especially true for woody plant species. Deer browsing at such high levels can reduce woody plant diversity by upwards of 60%. Especially hard hit are seedlings and saplings. In many areas, forests are growing older without any young trees to replace them.

What's more, their selectivity when it comes to what's on the menu means that forests are becoming more homogenous. Grasses, sedges, and ferns are increasingly replacing herbaceous cover gobbled up by deer. Also, deer appear to prefer native plants over invasives, leaving behind a sea of plants that local wildlife can't readily utilize. It's not just plants that are affected either. Excessive deer browse is creating trophic cascades that propagate throughout the food web.

For instance, birds and plants are intricately linked. Flowers attract insects and eventually produce seeds. These in turn provide food for birds. Shrubs provide food as well as shelter and nesting space, a necessary requisite for healthy bird populations. Other studies have shown that in areas that experience the highest deer densities songbird populations are nearly 40% lower than in areas with smaller deer populations. As deer make short work of our native plants, they are hurting far more than just the plants themselves. Every plant that disappears from the landscape is one less plant that can support wildlife.

Sadly, due to the elimination of large predators from the landscape, deer have no natural checks and balances on their populations other than disease and starvation. As we replace natural areas with manicured lawns and gardens, we are only making the problem worse. Deer have adapted quite well to human disturbance, a fact not lost on anyone who has had their garden raided by these ungulates. Whereas the deer problem is only a piece of the puzzle when it comes to environmental issues, it is nonetheless a large one. With management practices aimed more towards trophy deer than healthy population numbers, it is likely this issue will only get worse.

Photo Credit: tuchodi (http://bit.ly/1wFYh2X)

Further Reading:

http://aobpla.oxfordjournals.org/content/7/plv119.full

http://aobpla.oxfordjournals.org/content/6/plu030.full

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320705001722

Zoophagous Liverworts?

Photo by Matt von Konrat Ph.D - Biblioteca Digital Mundial (eol.org) licensed under CC BY 3.0

Mention the word "liverwort" to most folks and you are going to get some funny looks. However, mention it to the right person and you will inevitably be drawn into a world of deep appreciation for this overlooked branch of the plant kingdom. The world of liverworts is best appreciated with a hand lens or microscope.

A complete lack of vascular tissue means this ancient lineage is often consigned to humid nooks and crannies. Look closely, however, and you are in for lots of surprises. For instance, did you know that there are liverworts that may be utilizing animal traps?

Right out of the gates I need to say that the most current research does not have this labelled as carnivorous behavior. Nonetheless, the presence of such derived morphological features in liverworts is quite sensational. These "traps" have been identified in at least two species of liverwort, Colura zoophaga, which is native to the highlands of Africa, and Pleurozia purpurea, which has a much wider distribution throughout the peatlands of the world.

A liverwort “trap” showing the lid (L), water sac (wl). {SOURCE]

The traps are incredibly small and likely derived from water storage organs. What is different about these traps is that they have a moveable lid that only opens inward. In the wild it is not uncommon to find these traps full of protozoans as well as other small microfauna. Researchers aimed to find out whether or not this is due to chance or if there is some active capture going on.

Using feeding experiments it was found that some protozoans are actually attracted to these plants. What's more these traps do indeed function in a similar way to the bladders of the known carnivorous genus Utricularia. Despite these observations, no digestive enzymes have been detected to date. For now researchers are suggesting that this is a form of "zoophagy" in which animals lured inside the traps die and are broken down by bacterial communities. In this way, these liverworts may be indirectly benefiting from the work of the bacteria.

This is not unheard of in the plant world. In fact, there are many species of pitcher plants that utilize similar methods of obtaining valuable nutrients. Certainly the lack of nutrients in the preferred habitats of these liverworts mean any supplement would be beneficial.

Photo Credits: Matt von Konrat Ph.D - Biblioteca Digital Mundial (eol.org), HESS ET AL. 2005 (http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1639/6), and Sebastian Hess (http://virtuelle.gefil.de/s-hess/forsch.html)

Further Reading: [1]

The Curly-Whirly Plants of South Africa

Gethyllis villosa. Photo by Capetown Botanist: www.capetownbotanist.com

In a region of South Africa traditionally referred to as Namaqualand there exists a guild of plants that exhibit a strange pattern in their growth habits. These plants hail from at least eight different monocot families as well as the family Oxalidaceae. They are all geophytes, meaning they live out the driest months of the year as dormant, bulb-like structure underground. However, this is not the only feature that unites them.

A walk through this region during the growing season would reveal that members of this guild all produce leaves that at least one author has described as "curly-whirly." To the casual observer it would seem that they had left the natural expanse of the desert flora and entered into the garden of someone with very particular tastes.

What these plants have managed to do is to converge on a morphological strategy that allows them to take full advantage of their unique geographical location. The region along the coastal belt of Namibia is famous for being a "fog desert." Despite receiving very little rain, humid air blowing in from the southwestern Atlantic runs into colder air blowing down from the north and condenses, carrying fog inland. This produces copious amounts of dew.

Normally dew would be unavailable to most plants. It simply doesn't penetrate the soil enough to be useful for roots. This is where those curly-whirly leaves come in. Researchers have discovered that this leaf anatomy is specifically adapted for capturing and concentrating fog and dew. This has the effect of significantly improving their water budget in this otherwise arid region. What's more, the advantages are additive.

The most obvious advantage has to do with surface area. Curled leaves increase the amount of edge a leaf has. This provides ample area for capturing fog and dew. Also, by curling up, the leaves are able to reduce the overall size of the leaf exposed to the air, which reduces the amount of transpiration stress these plants encounter in their hot desert environment. Another advantage is direct absorption. Although no specific organs exist for absorbing water, the leaves of most of these species are nonetheless capable of absorbing considerable amounts.

Dipcadi crispum By roncorylus

Finally, each curled leaf acts like a mini gutter, channeling water to the base of the plant. Many of these plants have surprisingly shallow root zones. The lack of a deep taproot may seem odd until one considers the fact that dew dripping down from the leaves above doesn't penetrate too deeply into the soil. These roots are sometimes referred to as "dew roots."

I don't know about you but this may be one of the coolest plant guilds I have ever heard about. This is such a wonderfully clear example of just how strong of a selective pressure the combination of geography and climate can be. What's more, this is not the only region in the world where drought-tolerant plants have converged on this curly strategy. Similar guilds exist in other arid regions of Africa, as well as in Turkey, Australia, and Asia.

Albuca spiralis. Photo by Wolf G. licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Photo Credits: Cape Town Botanist (http://bit.ly/1PzPkP7), www.ispotnature.org, roncorylus (http://bit.ly/1PzPoi6), and Wolf G. (http://bit.ly/1n4Mo6b)

Further Reading: [1]

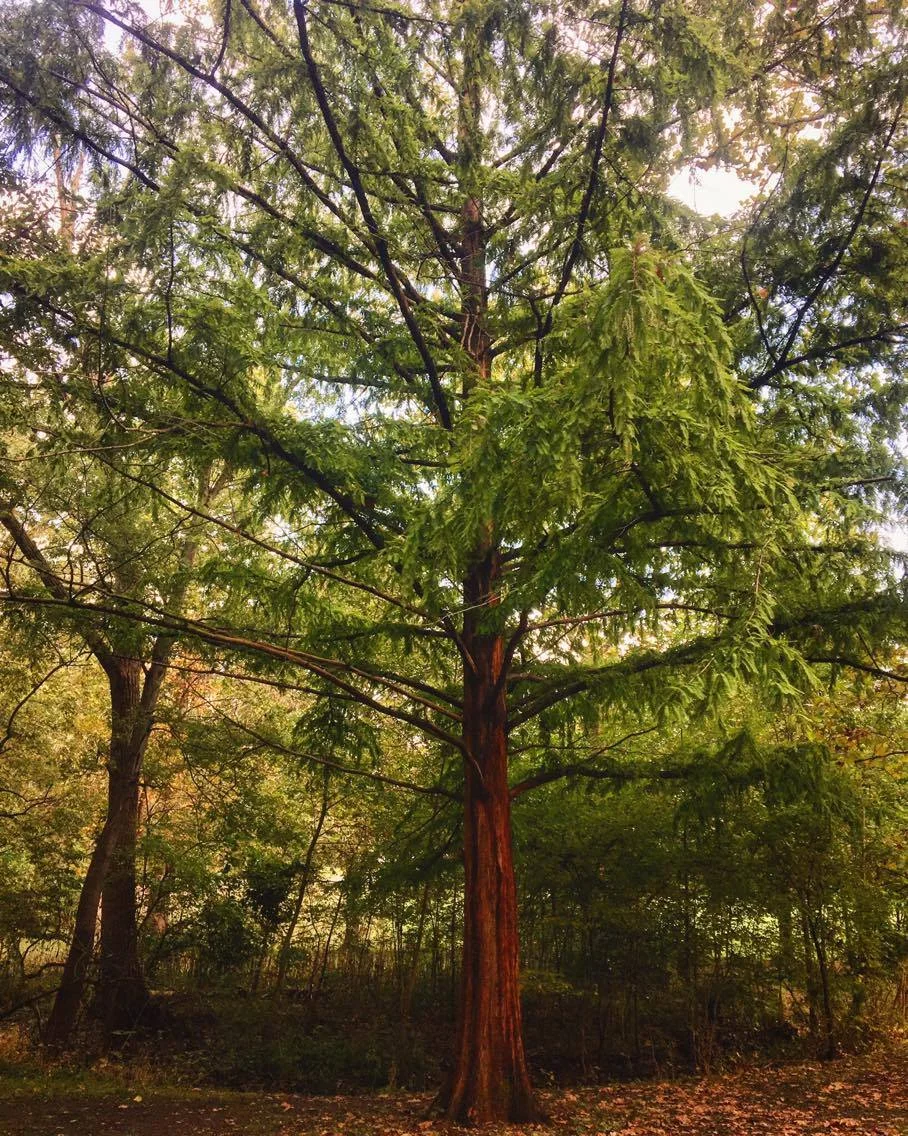

The Dawn Redwood

The dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) is one of the first trees that I learned to identify as a young child. My grandfather had one growing in his backyard. I always thought it was a strange looking tree but its low slung branches made for some great climbing. I was really into paleontology back then so when he told me this tree was a "living fossil" I loved it even more. It would be many years before I would learn the story behind this interesting conifer.

Photo by Ruth Hartnup licensed under CC BY 2.0

Along with the coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), the dawn redwood makes up the subfamily Sequoioideae. Compared to its cousins, the dawn redwood is the runt, however, with a max height of around 200 feet (60 meters), a mature dawn redwood is still an impressive sight.

Until 1944 the genus Metasequoia was only known from fossil evidence. As with the other redwood species, the dawn redwood once realized quite a wide distribution. It could be found throughout the northern regions of Asia and North America. In fact, the fossilized remains of these trees make up a significant proportion of the fossils found in the Badlands of North Dakota.

Fossil evidence dates from the late Cretaceous into the Miocene. The genus hit its widest distribution during a time when most of the world was warm and tropical. Evidence would suggest that the dawn redwood and its relatives were already deciduous by this time. Why would a tree living in tropical climates drop its leaves? Sun.

Regardless of climate, axial tilt nonetheless made it so that the northern hemisphere did not see much sun during the winter months. It is hypothesized that the genus Metasequoia evolved its deciduous nature to cope with the darkness. Despite its success, fossil evidence of this genus disappears after the Miocene. For this reason, Metasequoia was thought to be an extinct lineage.

Photo by Georgialh licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

All of this changed in 1943 when a Chinese forestry official collected samples from a strange tree growing in Moudao, Hubei. Though the samples were quite peculiar, World War II restricted further investigations. In 1946, two professors looked over the samples and determined them to be quite unique indeed. They realized that these were from a living member of the genus Metasequoia.

Thanks to a collecting trip in 1948, seeds of this species were distributed to arboretums around the world. The dawn redwood would become quite the sensation. Everyone wanted to own this living fossil. Today we now know of a few more populations. However, most of these are quite small, consisting of around 30 trees. The largest population of this species can be found growing in Xiaohe Valley and consists of around 5,000 individuals. Despite its success as a landscape tree, the dawn redwood is still considered endangered in the wild. Demand for seeds has led to very little recruitment in the remaining populations.

An Orchid With Body Odor

Photo by Ryan LeBlanc licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Aside from ourselves, mosquitoes may be humanity's largest threat. For many species of mosquito, females require blood to produce eggs. As such, they voraciously seek out animals and in doing so can spread deadly diseases. They do this by homing in on the chemicals such as CO2 and other compounds given off by animals. What is less commonly known about mosquitoes is that blood isn't their only food source. Males and females alike seek out nectar as source of carbohydrates.

Though mosquitoes visit flowers on a regular basis, they are pretty poor pollinators. However, some plants have managed to hone in on the mosquito as a pollinator. It should be no surprise that some orchids utilize this strategy. Despite knowledge of this relationship, it has been largely unknown exactly how these plants lure mosquitoes to their flowers. Recent work on one orchid, Platanthera obtusata, has revealed a very intriguing strategy to attract their mosquito pollinators.

This orchid produces human body odor. Though it is undetectable to the human nose, it seems to work for mosquitoes. Researchers at the University of Washington were able to isolate the scent compounds and found that they elicited electrical activity in the mosquitoes antennae. Though more work needs to be done to verify that these compounds do indeed attract mosquitoes in the wild, it nonetheless hints at one of the most unique ruses in the floral world.

Photo Credit: Kiley Riffell and Jacob W. Frank

Further Reading:

http://bit.ly/1JXP2jk

![Traverse section of a Gunnera stem showing cyanobacteria colonies (C) and the cup-like structures (S) where they enter the stem. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1554817873192-NHJDSUCEACL2Q9TLEJUP/gunnera.JPG)

![A liverwort “trap” showing the lid (L), water sac (wl). {SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1453484005585-XO0ZD7MMGIVHXPW0JU5M/image-asset.jpeg)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1453483994540-FO0ROSLCBG9A6TRN9HHJ/image-asset.jpeg)