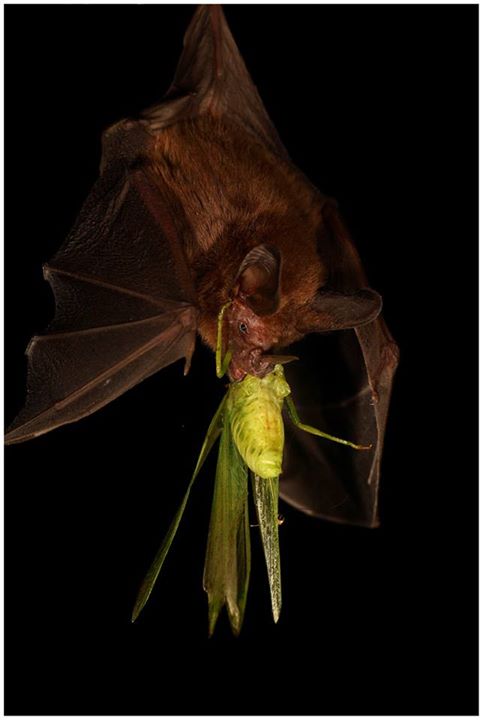

Photo by Sonnentau licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

This switch from more traditional farming practices to industrialized monocultures has left a damaging legacy on ecosystems around the globe. This is especially true for unwanted plants. Species that once grew in profusion are now sprayed and tilled out of existence. Nowhere has this been better illustrated than for a lovely little plant known commonly as the corncockle (Agrostemma githago).

This species was once a common weed in European wheat fields. Throughout much of the 19th and early 20th century, it was likely that most wheat sold contained a measurable level of corncockle seed. Its pink flowers would have juxtaposed heavily against the amber hue of grain. Indeed, its habit of associating with wheat has lead to its introduction around the globe. It can now be found growing throughout parts of North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

However, in its home range of Europe, the corncockle isn't doing so well. The industrialization of farming dealt a huge blow to corncockle ecology. The broad-scale application of herbicides wreaked havoc on corncockle populations. Much more detrimental was the switch to winter wheat, which caused a decoupling between harvest time and seed set for the corncockle. Whereas it once synced quite nicely with regular wheat harvest, winter wheat is harvested before corncockle can set seed. As such, corncockle has become extremely rare throughout its native range and was even thought to be extinct in the UK.

A discovery in 2014 changed all of that. National Trust assistant ranger Dougie Holden found a single plant flowering near a lighthouse. Extensive use of field guides and keys confirmed that this plant was indeed a corncockle, the first seen blooming in the UK in many decades. It is likely that the sole plant grew from seed churned up by vehicle traffic the season before.

Photo Credit: sonnentau (bit.ly/1qo3XQK)

Further Reading:

Clapham, A.R., Tutin, T.G. and Warburg, E.F. 1968. Excursion Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press