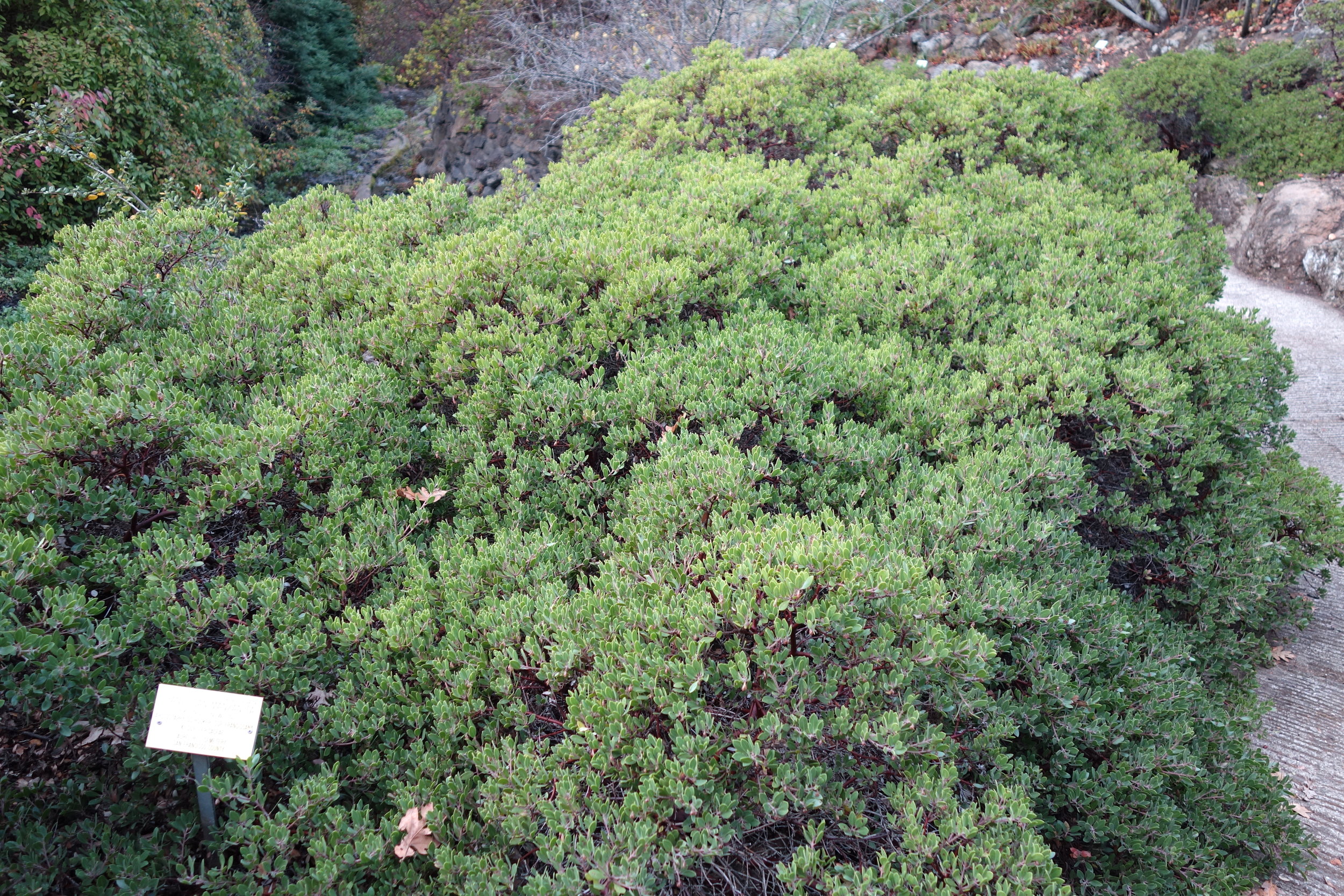

Photo by Stan Shebs licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The chance to save a species from certain extinction cannot be wasted. When the opportunity presents itself, I believe it is our duty to do so. Back in 2010, such an opportunity presented itself to the state of California and what follows is a heroic demonstration of the lengths dedicated individuals will go to protect biodiversity. Thought to be extinct for 60 years, the Franciscan manzanita (Arctostaphylos franciscana) has been given a second chance at life on this planet.

California is known the world over for its staggering biodiversity. Thanks to a multitude of factors that include wide variations in soil and climate types, California boasts an amazing variety of plant life. Some of the most Californian of these plants belong to a group of shrubs and trees collectively referred to as 'manzanitas.' These plants are members of the genus Arctostaphylos, which hails from the family Ericaceae, and sport wonderful red bark, small green leaves, and lovely bell-shaped flowers. Of the approximately 105 species, subspecies, and varieties of manzanita known to science, 95 of them can be found growing in California.

It has been suggested that manzanitas as a whole are a relatively recent taxon, having arisen sometime during the Middle Miocene. This fact complicates their taxonomy a bit because such a rapid radiation has led manzanita authorities to recognize a multitude of subspecies and varieties. In California, there are also many endemic species that owe their existence in part to the state's complicated geologic history. Some of these manzanitas are exceedingly rare, having only been found growing in one or a few locations. Sadly, untold species were probably lost as California was settled and human development cleared the land.

Such was the case for the Franciscan manzanita. Its discovery dates back to the late 1800's. California botanist and manzanita expert, Alice Eastwood, originally collected this plant on serpentine soils around the San Francisco Bay Area. In the years following, the growing human population began putting lots of pressure on the surrounding landscape.

Photo by Daderot (public domain)

Botanists like Eastwood recognized this and went to work doing what they could to save specimens from the onslaught of bulldozers. Luckily, the Franciscan manzanita was one such species. A few individuals were dug up, rooted, and their progeny were distributed to various botanical gardens. By the 1940's, the last known wild population of Franciscan manzanita were torn up and replaced by the unending tide of human expansion into the Bay Area.

It was apparent that the Franciscan manzanita was gone for good. Nothing was left of its original populations outside of botanical gardens. It was officially declared extinct in the wild. Decades went by without much thought for this plant outside of a few botanical circles. All of that changed in 2009.

It was in 2009 when a project began to replace a stretch of roadway called Doyle Drive. It was a massive project and a lot of effort was invested to remove the resident vegetation from the site before work could start in earnest. Native vegetation was salvaged to be used in restoration projects but most of the clearing involved the removal of aggressive roadside trees. A chipper was brought in to turn the trees into wood chips. Thanks to a bit of serendipity, a single area of vegetation bounded on all sides by busy highway was spared from wood chip piles. Apparently the only reason for this was because a patrol car had been parked there during the chipping operation.

Cleared of tall, weedy trees, this small island of vegetation had become visible by road for the first time in decades. That fall, a botanist by the name of Daniel Gluesenkamp was driving by the construction site when he noticed an odd looking shrub growing there. Luckily, he knew enough about manzanitas to know something was different about this shrub. Returning to the site with fellow botanists, Gluesenkamp and others confirmed that this odd shrubby manzanita was in fact the sole surviving wild Franciscan manzanita. Needless to say, this caused a bit of a stir among conservationists.

The shrub had obviously been growing in that little island of serpentine soils for quite some time. The surrounding vegetation had effectively concealed its presence from the hustle and bustle of commuters that crisscross this section of on and off ramps every day. Oddly enough, this single plant likely owes its entire existence to the disturbance that created the highway in the first place. Manzanitas lay down a persistent seed bank year after year and those seeds can remain dormant until disturbance, usually fire but in this case road construction, awakens them from their slumber. It is likely that road crews had originally disturbed the serpentine soils just enough that this single Franciscan manzanita was able to germinate and survive.

The rediscovery of the last wild Franciscan manzanita was bitter sweet. On the one hand, a species thought extinct for 60 years had been rediscovered. On the other hand, this single individual was extremely stressed by years of noxious car exhaust and now, the sudden influx of sunlight due to the removal of the trees that once sheltered it. What's more, this small island of vegetation was doomed to destruction due to current highway construction. It quickly became apparent that if this plant had any chance of survival, something drastic had to be done.

Many possible rescue scenarios were considered, from cloning the plant to moving bits of it into botanical gardens. In the end, the most heroic option was decided on - this single Franciscan manzanita was going to be relocated to a managed natural area with a similar soil composition and microclimate.

Moving an established shrub is not easy, especially when that particular individual is already stressed to the max. As such, numerous safeguards were enacted to preserve the genetic legacy of this remaining wild individual just in case it did not survive the ordeal. Stem cuttings were taken so that they could be rooted and cloned in a lab. Rooted branches were cut and taken to greenhouses to be grown up to self-sustaining individuals. Numerous seeds were collected from the surprising amount of ripe fruits present on the shrub that year. Finally, soil containing years of this Franciscan manzanita's seedbank as well as the microbial community associated with the roots, were collected and stored to help in future reintroduction efforts.

Finally, the day came when the plant was to be dug up and moved. Trenches were dug around the root mass and a dozen metal pipes were driven into the soil 2 feet below the plant so that the shrub could safely be separated from the soil in which it had been growing all its life. These pipes were then bolted to I-beams and a crane was used to hoist the manzanita up and out of the precarious spot that nurtured it in secret for all those years.

Upon arriving at its new home, experts left nothing to chance. The shrub was monitored daily for the first ten days of its arrival followed by continued weekly visits after that. As anyone that gardens knows, new plantings must be babied a bit before they become established. For over a year, this single shrub was sheltered from direct sun, pruned of any dead and sickly branches, and carefully weeded to minimize competition. Amazingly, thanks to the coordinated effort of conservationists, the state of California, and road crews, this single individual lives on in the wild.

Of course, one single individual is not enough to save this species from extinction. At current, cuttings, and seeds provide a great starting place for further reintroduction efforts. Similarly, and most importantly, a bit of foresight on the part of a handful of dedicated botanists nearly a century ago means that the presence of several unique genetic lines of this species living in botanical gardens means that at least some genetic variability can be introduced into the restoration efforts of the Franciscan manzanita.

In an ideal world, conservation would never have to start with a single remaining individual. As we all know, however, this is not an ideal world. Still, this story provides us with inspiration and a sense of hope that if we can work together, amazing things can be done to preserve and restore at least some of what has been lost. The Franciscan manzanita is but one species that desperately needs our help an attention. It is a poignant reminder to never give up and to keep working hard on protecting and restoring biodiversity.

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4]

Further Reading: [1] [2] [3] [4]