Floral traits can provide us with insights into the types of pollinators most suited for the job. For many flowering plants, the relationship is relatively easy to understand, but check out the flowers of Scybalium fungiforme. You would be completely excused for not even realizing that these bizarre structures belonged to a plant. The anatomy of those flowers would leave most of asking “what on Earth do they attract?” The answer to this are opossums!

Scybalium fungiforme hails from a peculiar family of parasitic plants called Balanophoraceae and is native to the Atlantic forests of Brazil. Members of this family can be found in tropical regions around the globe and all of them are obligate root holoparasites. Essentially this means that all one ever sees of these plants are their strange flowers. The rest of the plant lives within the vascular system of a host plant’s roots.

The adorable big-eared opossums (Didelphis aurita).

Scybalium fungiforme is particularly strange in that its flowers are covered in scale-like bracts. As such, accessing the flowers would be difficult for most animals. Because its strange blooms superficially resemble some marsupial and rodent pollinated Proteaceae in Australian and South Africa, predictions of a non-flying mammal pollination syndrome were about the only explanations that made sense. Now, with the help of night vision cameras, this prediction has been vindicated.

They key to this unique pollination syndrome lies in those bracts and an interesting aspect of opossum anatomy. Until the scale-like bracts are removed, not much is able to access the floral parts inside. Luckily big-eared opossums (Didelphis aurita) come equipped with opposable toes on their back feet. Upon locating the flowers of S. fungiforme, the opossum uses its back feet to remove the bracts. This unveils a bounty of nectar within. As the opossum feeds, its furry little snout gets covered in pollen. When the opossum visits subsequent flowers throughout the night, pollination is achieved.

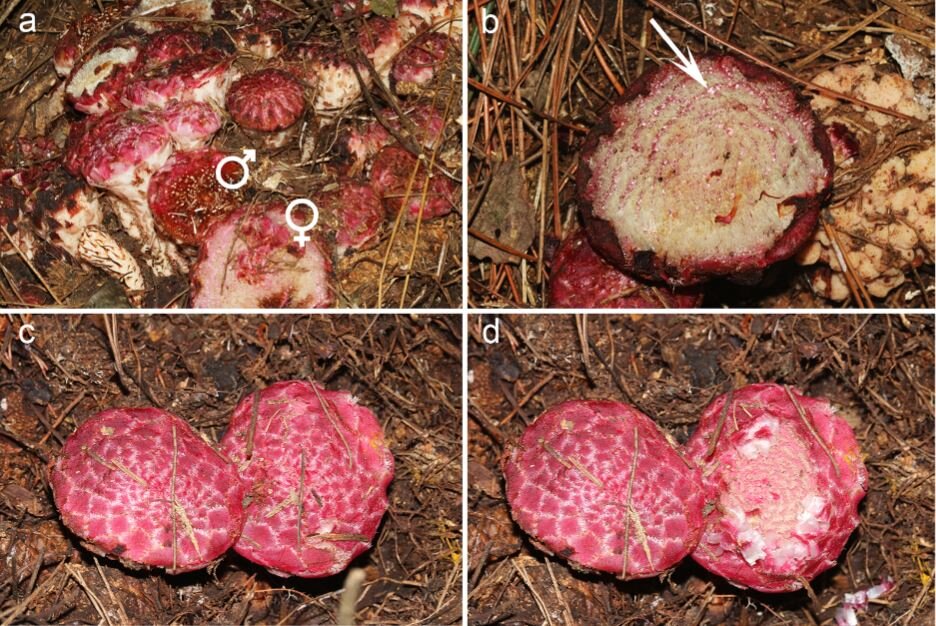

Floral visitors of Scybalium fungiforme. b) The big-eared opossum, Didelphis aurita drinking nectar on a plant with five inflorescences (one male and four females). c) The montane grass mouse, Akodon montensis, visiting a plant with about 10 inflorescences and drinking nectar on a female one. d) The Violet-capped Woodnymph hummingbird, Thalurania glaucopis visiting a male and e) a female inflorescence. f) detail of an A. angulata wasp manipulating a male flower to eat pollen. g) Agelaia angulate visiting a female inflorescence with the head inserted among flowers to reach the nectar secreted in the inflorescence receptaculum.

Interestingly, activity doesn’t end when the opossums are done. Enough nectar often remains by the next day that a suite of other animals come to pay a visit to these strange blooms. Day time visitation of S. fungiforme consisted largely of wasps, bees, and even a mouse or two. Researchers were also lucky enough to witness Violet-capped Woodnymph hummingbirds (Thalurania glaucopis) repeatedly visit the flowers for a sip of nectar. It would appear that although the main pollinators of this strange parasite are opossums, the removal of the bracts opens up the flowers for plenty of secondary pollinators as well.

Though this is by no means the only plant to be pollinated by non-flying mammals, this pollination syndrome certainly broadens our understanding of the evolution of pollination syndromes.