Photo by LynnK827 licensed by CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I love the spike in popularity of houseplants. The more popular indoor gardening becomes, the more plants become available for obsessive growers such as myself. If you are like me, then learning about the ecological and evolutionary history of the plants you keep makes them all the more special. Take, for instance, a small group of scrambling succulents affectionately referred to as “string of pearls,” “string of bananas,” and “string of tears.” These all make incredible houseplants if given the proper care, but they become all the more interesting when you realize that they are distant cousins of the dandelions growing in your yard.

That’s right, each of these species are highly derived members of the daisy family (Asteraceae). Their taxonomy has been a bit wonky over the years. When I first took interest in these succulents, they resided in the genus Senecio. Some authors have suggested moving them into the genus Kleinia or Cacalia, but current systematics suggests they belong in a genus of their own - Curio. Inspection of the relationships within this group reveals that closely related species have evolved slightly different growing habits. The plants I will be focusing on for this article each resemble creeping vines but many of their close relatives are less vine-like but nonetheless still creep along the ground. For the sake of this piece, I am going to stick with the genus Senecio because, regardless of their taxonomic placement, the “sting of” clade is super fascinating from an ecological standpoint.

Senecio citriformis photo by Salchuiwt licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0

Senecio radicans photo by KENPEI licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

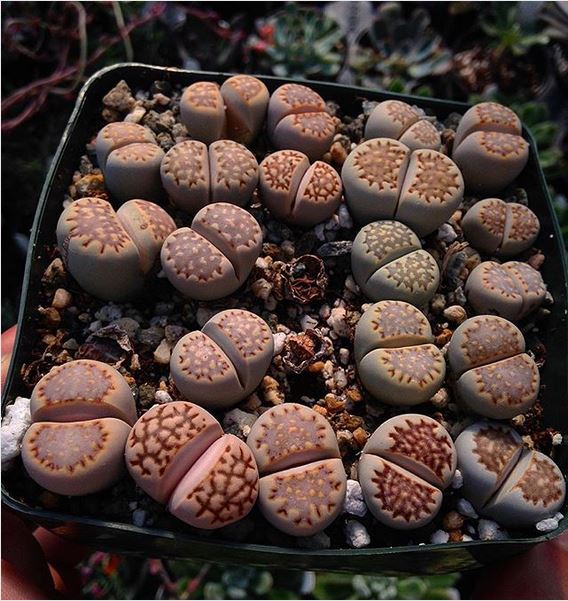

All of these stringy plants hail from arid regions of South Africa. In the wild, they mostly scramble over rocks and bushes, often emerging out of cracks in rock in search of the right microclimate. Their oddly shaped, succulent leaves are an evolutionary adaptation to the tough conditions in which they evolved. The most leaf-like anatomy belongs to that of the string of bananas (S. radicans). Each leaf of S. radicans is shaped like a tiny green banana. More extreme versions of leaf morphology are found in the string of tears (S. citriformis) and string of pearls (S. rowleyanus & S. herreianus). The leaves of these three species resemble peas in shape, size and color. The leaves of S. rowleyanus are more spherical in shape (pearls), whereas the leaves of S. citriformis taper towards the tip (tears).

Senecio herreianus photo by Frank Vincentz licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

Though all of these species grow in dry habitats, the more spherical shaped leaves of S. rowleyanus and S. citriformis are thought to be best adapted for drought. In growing spherical leaves, these plants are taking advantage of the surface area to volume ratio of a sphere. The benefit of this is that these species are able to maximize water storage while minimizing the amount of leaf surface exposed to the blistering sun. This way the leaves are able to maintain high levels of photosynthesis without overheating, all the while reducing leaf temperature.

In each of these species, the surface or adaxial side of the leaf exhibits a translucent window that runs the length of the leaf. It has long been hypothesized that leaf windows allow light to transmit into deep into the interior of the leaf where the photosynthetic machinery resides. More recent experiments on window-leaved succulents suggests that reality is not that simple. Instead, these windowed surfaces appear to allow the plant to maintain healthy levels of photosynthesis without the damaging their leaves via overheating.

Photo by Frank Vincentz licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

When plants reach maturity, flowering can be prolific. Thin stems topped with tiny composite heads of cream-colored flowers erupt from the mat of vegetation. Then and only then do these plants readily reveal their placement within the daisy family. The inflorescence is made up entirely of discoid flowers. There are no rays like that of a sunflower. The flowers themselves are said to produce a pleasant odor frequently described as sweet and spicy. After pollination, the flowers give way to seeds topped with a parachute-like pappus that will carry them far and wide on the wind.

Learning about the natural history of these plants has given me a whole new appreciation of these strange, succulent members of the daisy family. What’s more, there is a whole world of succulent asters out there (a post for a later time) and many of them are equally as fascinating and beautiful.