Photo by moggafogga licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Flowers paint the world in a dazzling array of colors. Some of these we can see and others we cannot. Many plants paint their blooms in special pigments that absorb ultraviolet light, revealing intriguing patterns to pollinators like bees and even some birds that can see well into the UV part of the electromagnetic spectrum. UV absorbing pigments do more than attract pollinators. They can also protect sensitive reproductive organs from UV radiation. By studying these pigments, scientists are finding that many different plants are changing their floral displays in response to changes in their environment.

Growing up I heard a lot about the hole in the ozone layer. Prior to the 1980’s humans were pumping massive quantities of ozone-depleting chemicals such as halocarbon refrigerants, solvents, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) into the atmosphere, creating a massive hole in the ozone layer. Though ozone depletion has improved markedly thanks to regulations placed on these chemicals, it doesn’t mean that life has not had to adapt. As you may remember from your grade school science class, Earth’s ozone layer helps protect life from the damaging effects of ultraviolet radiation. UV radiation damages sensitive biological molecules like DNA so it is in any organisms best interest to minimize its impacts.

UV absorbing pigments in floral tissues can do just that. In addition to attracting pollinators, these pigments act as a sort of sun screen, reducing the likelihood of damaging mutations. By studying 1,238 herbarium specimens collected between 1941 and 2017 representing 42 different species, scientists discovered a startling change in the amount of UV pigments produced in their flowers.

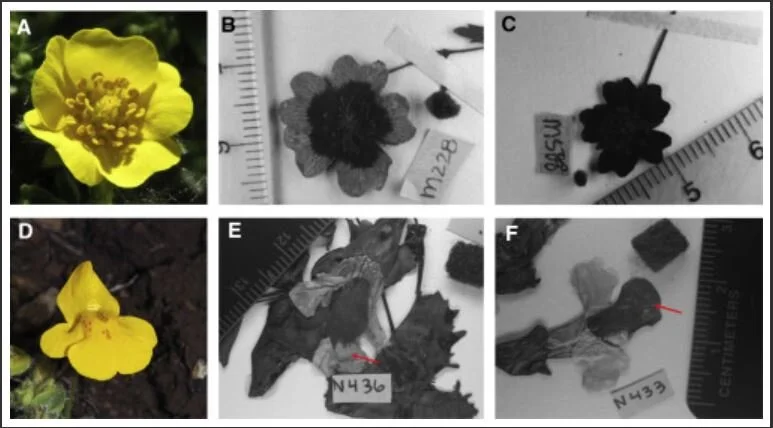

Exemplary images for a species with anthers exposed to ambient conditions, Potentilla crantzii (A–C) and a species with anthers protected by floral tissue Mimulus guttatus (D–F). Darker petal areas possess UV-absorbing compounds whereas lighter areas are UV reflective and lack UV-absorbing compounds. (B) and (E) display a reduced area of UV-absorbing pigmentation on petals compared to (C) and (F). Arrows in (E) and (F) highlight differences in pigment distribution on the lower petal lobe of M. guttatus. [SOURCE]

Across North America, Europe, and Australia, the amount of UV pigments produced in the flowers tended to increase by an average of 2% per year from 1941 to 2017. These increases in UV pigments occurred in tandem with decreases in the ozone layer. It would appear that, to protect their reproductive organs from harmful UV rays, many plants were increasing these protective pigments.

However, changes in UV pigments were not uniform across all the species they examined. Plants that produce saucer or cup-shaped flowers experienced the greatest increases in UV pigments. This makes complete sense as this sort of floral morphology exposes the reproductive organs directly to the sun’s rays. The pattern reversed when scientists examined flowers whose petals enclose the reproductive organs such as those seen in bladderworts (Utricularia spp.). UV pigments in flowers that conceal their reproductive organs actually decreased over this time period.

The reason for this comes down to a trade off inherent in UV pigments. Absorbing UV radiation is a great way to reduce its impact on sensitive tissues but it also leads to increased temperatures. For plants that enclose their reproductive organs within their petals, this can lead to overheating. Heat can also be very damaging to floral structures so it makes complete sense that species with this type of floral morphology would demonstrate the opposite pattern. By reducing the amount of UV absorbing pigments in their flowers, plants like bladderworts are able to minimize the effect of increased radiation and temperatures that occurred over this time period.

How changes in floral pigments are affecting pollination rates for these plants is another story entirely. Because UV pigments also help attract certain pollinators, there is always a chance that the appearance of some of these flowers may also be changing over time. Now that we know this is occurring across a wide range of unrelated plants, research can now be aimed at tackling questions like this.

Further Reading: [1]