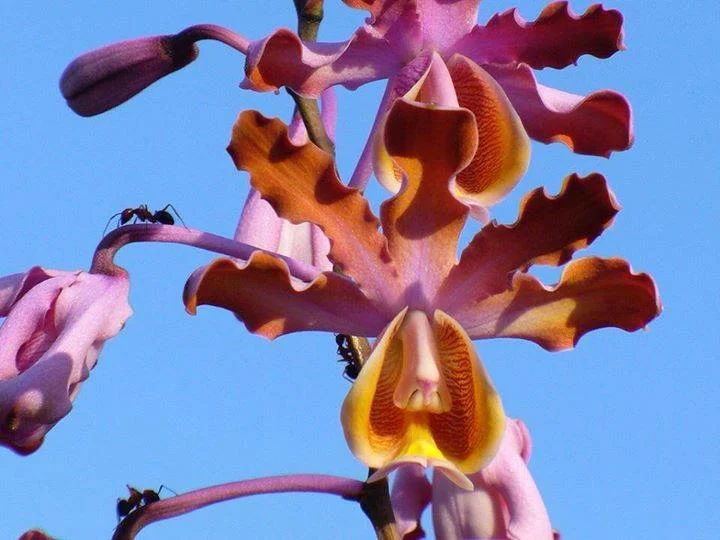

Photo by Scott Zona licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

I am beginning to think that there is no strategy for survival that is off-limits to the orchid family. Yes, as you may have figured out by now, I am a bit obsessed with these plants. Can you really blame me though? Take for instance Schomburgkia tibicinis (though you may also see it listed under the genera Laelia or more accurately, Myrmecophila). These North, Central, and South American orchids are more commonly referred to as cow-horn orchids because they possess hollow pseudobulbs that have been said to been used by children as toy horns. What is the point of these hollow pseudobulbs?

A paper published back in 1989 in the American Journal of Botany found the answer to that question. As it turns out, ants are quite closely associated with orchids in this genus. They crawl all over the flowers, feeding on nectar. The relationship goes much deeper though. If you were to cut open one of these hollow pseudobulbs, you would find ant colonies living within them. The ants nest inside and often pile up great stores of food and eventually waste within these chambers. The walls of the chambers are lined with a dark tissue that was suspect to researchers.

Using radioactively labeled ants, the researchers found that the orchids were actually taking up nutrients from the ant middens! What's more, nutrients weren't found solely in adjacent tissues but also far away, in the actively growing parts of the roots. These orchids are not only absorbing nutrients from the ants but also translocating it to growing tissues.

While orchids without a resident ant colony seem to do okay, it is believed that orchids with a resident ant colony do ever so slightly better. This makes sense. These orchids grow as epiphytes on trees, a niche that is not high in nutrients. Any additional sources of nutrients these plants can get will undoubtedly aid in their long-term survival. Also, because the ants use the orchids as a food source and a nest site, they are likely defending them from herbivores.

Photo Credit: Scott.Zona (http://bit.ly/1hvWiGX)

Further Reading:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2444355