Nolana humifusa (Solanaceae) Photo by Michael Wolf licensed by GNU Free Documentation License

Peru’s coastal deserts are some of the driest places on Earth. Most of the water they receive comes not from rain but rather fog rolling in off the ocean. These fog-fed habitats are known as Lomas and they support a surprising diversity of plant species. Still, life in the Lomas is no treat so plants growing there need a bit more than a tough disposition to get by. Many components of the Lomas flora rely on favorable microclimates to survive long enough to reproduce. Recently it has been found that a few species of burrowing birds are responsible for creating some of these favorable microclimates.

The beneficial effects of burrowing or “fossorial” animals on plant diversity has many examples in nature. This is especially true in harsh climates. The act of burrowing disturbs the surrounding soil and can expose nutrient-rich soils as well as increase hydrology. However, more than just mammals burrow. As such, researchers wanted to investigate the role of burrowing birds on Lomas plant diversity.

A pair of burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia) Photo by Ron Knight licensed by CC BY 2.0

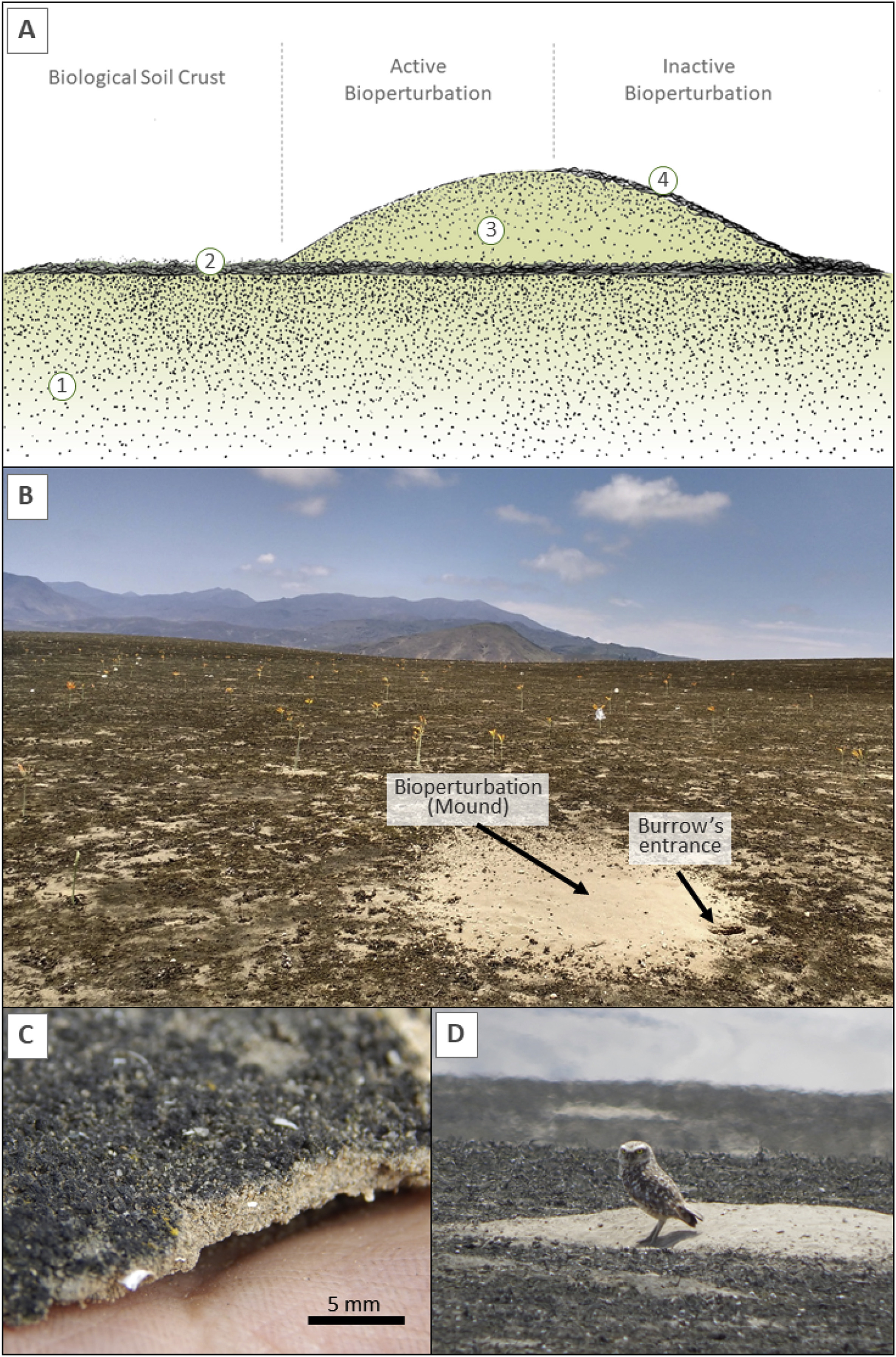

The birds in this study consist of one owl - the burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), and two species of miner birds (Geositta peruviana & G. maritima). Instead of nesting in trees, which are few and far between in such arid habitats, these birds nest in the ground. To do so, they excavate burrows. As they excavate, these birds break up the thin biocrust of cyanobacteria that carpets undisturbed stretches of sand. This biocrust is an immensely important component of the local ecology. It stabilizes sandy soils and increases their fertility. It also has a considerable impact on water infiltration, runoff, albedo, and temperature of the soil.

The greyish miner (Geositta maritima)

The coastal miner (Geositta peruviana) Photo by Berichard licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0

Taken together, it is easy to see how large patches of biocrust can either promote or inhibit plant germination and growth. Some species perform well under such conditions while others do not. This is why researchers were so interested in burrowing birds. By breaking up the biocrust and constructing mounds outside of their burrows, these birds are changing the microclimates of the surrounding area. This creates a heterogeneous patchwork of soil types that in turn influence the plant species that can grow and survive.

It turns out, burrowing birds on the Peruvian coast are having considerable effects on local plant diversity. By studying the soil properties around burrows and comparing it to undisturbed soil patches nearby, researchers were able to show that the plant communities living in these areas are in fact different. For starters, despite undisturbed soils having far more seeds in the soil seed bank than burrow mound soils, far more plants germinated and grew on the mounds than in the biocrusts. Also, though the seed bank of the mounds was largely comprised of similar species to that of the undisturbed soils, the seeds of species that produce bird-dispersed berries such as Solanum montanum were more abundant in the mound soil.

Fuertesimalva peruviana (Malvaceae) Photo by Jose Roque licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

In terms of seedlings, mound soils not only exhibited higher seedling emergence, they also exhibited a higher species richness than the undisturbed biocrust soils nearby. The benefits of growing in the mound soils were most apparent for three plant species in particular: Cistanthe paniculata (Montiaceae), S. montanum (Solanaceae), and Fuertesimalva peruviana (Malvaceae). It appears that these species are much more likely to germinate and survive in and around the burrows than they are in the surrounding landscape. Such a boost to growth and survival, however marginal, means a lot in such a harsh, uninviting landscape.

Even more incredible is how specific burrow microclimates can be. Plants growing on the mounds didn’t do so in a uniform way. Instead, tiny variations in the soil of the burrow mound appeared to make a huge difference for plants. Soils near the entrance of an active burrow are disturbed far more often than soils on the backside of the mound. As such, more plants were found growing on the backside of the mound, demonstrating yet again how slight improvements in favorable microclimates can have astounding impacts on plant survival and diversity.

A. Soil profiles of the studied treatments. B. Landscape of the study area. The lower site of the hills is covered in biocrust except where it is disturbed by birds' burrows (Bioperturbation labeled in the picture). C. Dark cyanobacterial biological soil crust that covers the study site. D. Burrowing owl Athene cunicularia standing on its bioperturbation. [SOURCE}

The reason some plants do much better in disturbed soils over those covered in cyanobacteria biocrust are still not entirely clear. It is likely that some plants simply can’t break through the biocrust as they germinate. It is also possible that the seeds of some of these species simply can’t break through the biocrust to even make it into the soil seedbank. Not only would this cause them to blow around, it also means that they aren’t contacting the soil enough to imbibe water and germinate. Despite containing fewer seeds, the act of digging a burrow may loosen up the soil enough so that seeds are properly buried and thus can maintain good soil to seed contact for long enough to promote germination and growth.

All in all it appears that these three bird species are important ecosystem engineers across the Lomas of the Peruvian coast. By creating a patchwork of different soil properties, these birds are essentially creating a patchwork of different habitats that support different plant species. Take the birds away and it is reasonable to assume that plant diversity would decline. This is yet another important reminder of how interconnected the natural world truly is. It is also an important reminder of why habitat, rather than species-specific conservation efforts should be a much higher priority than it is today. Please, support a land conservation agency today!

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]

Further Reading: [1]