Photo by mbarisson licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

When you think of gardening, alligators don’t readily jump to mind. Hang out long enough in places like the Everglades and that might change. I was only recently introduced to the concept of a “gator hole” and I must say, I was surprised what a quick search of the literature revealed. It turns out that alligators are important ecosystem engineers and do a wonderful job at increasing plant diversity in the wetlands they inhabit.

Throughout southeastern North America, gators change their behaviors with the seasons. During the rainy season, alligators can be found floating in open water or sunning themselves on land. Except when hunting, they don’t seem to do anything with much urgency. Their activity level changes during the dry season when water is in short supply. Gators don’t sit back and let nature take its course. They spring into action and create their own aquatic refuges.

As the surrounding landscape begins to dry, gators will excavate holes or pits in the soggy ground called gator holes. These holes hold onto water when most of the surrounding landscape isn’t. The process of digging a gator hole may seem destructive but it all must be placed in the context of the surrounding environment. Most gator habitat exists in low lying areas. In places like the Everglades, there isn’t much topography to speak of. When a gator excavates a gator hole, it creates variation in both hydrology and soil conditions.

Photo by Anita Gould licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

Soils that have built up over time are lifted out of the hole and piled into mounds. Mounded soils are not only rich in nutrients, they also dry at different rates, creating a gradient in water availability. Plants that normally can’t germinate and grow in saturated soils find suitable spots to live up on the soil mounds while emergent aquatic vegetation fills in along the parameter. Plants that normally prefer to grow in deeper water can also establish within the gator hole itself. In the midst of fairly uniform marsh vegetation, a gator hole quickly becomes a hotbed of plant diversity. The differences in vegetation can be so stark compared to the surrounding landscape that some scientists can actually map gator holes using aerial scans simply by measuring the differences in infrared radiation given off by the leaves of all the different plants that establish around them.

Of course, all of that plant diversity has a huge effect on other organisms as well. Gator holes become important areas for various reptiles, amphibians, birds, and so much more. The paths that alligators take to and from their holes even act like fire breaks, changing the way fire moves through the landscape, which only increases the heterogeneity of the immediate area. Fish, though occasionally eaten, greatly benefit from the stability of water levels within a gator hole. All in all, gator holes are extremely important habitats. Not only do they support a high diversity of plants and animals alike, they make places like the Everglades even more dynamic than they already are.

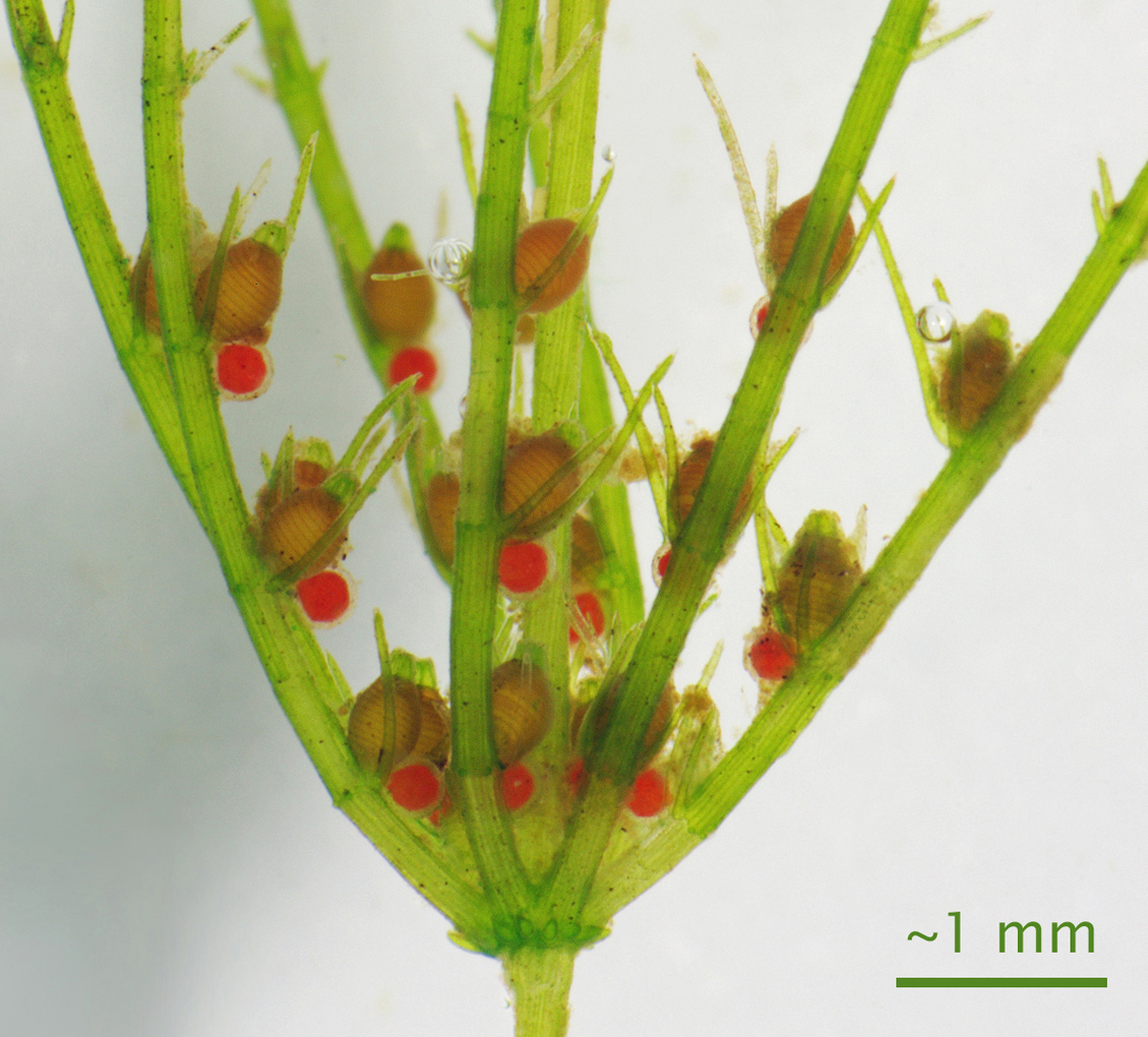

![After pollination, the stem of the female flower coils up, drawing the ripening ovaries safely underwater. Photo by Peter M. Dziuk [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1565792376405-64JD8XOEZI9QIVPB430T/vallisneria-americana-15-13.jpg)

![An example of the soda bottle terrariums. Photo by Kara Nelson [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1514928056661-E031RMQD8KDRVW6RCINO/image-asset.png)

![Photo by Keith Bradley kab_g_amphiantha_1012 March Forty Acre Rock Heritage Preserve Lancaster County SC [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1491873678294-OU79283XPNT3QWCWVJN2/image-asset.jpeg)

![[SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1477931674122-ZI5O0OLUMUU2ZC81XIY5/image-asset.jpeg)