Photo by Geir K. Edland licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

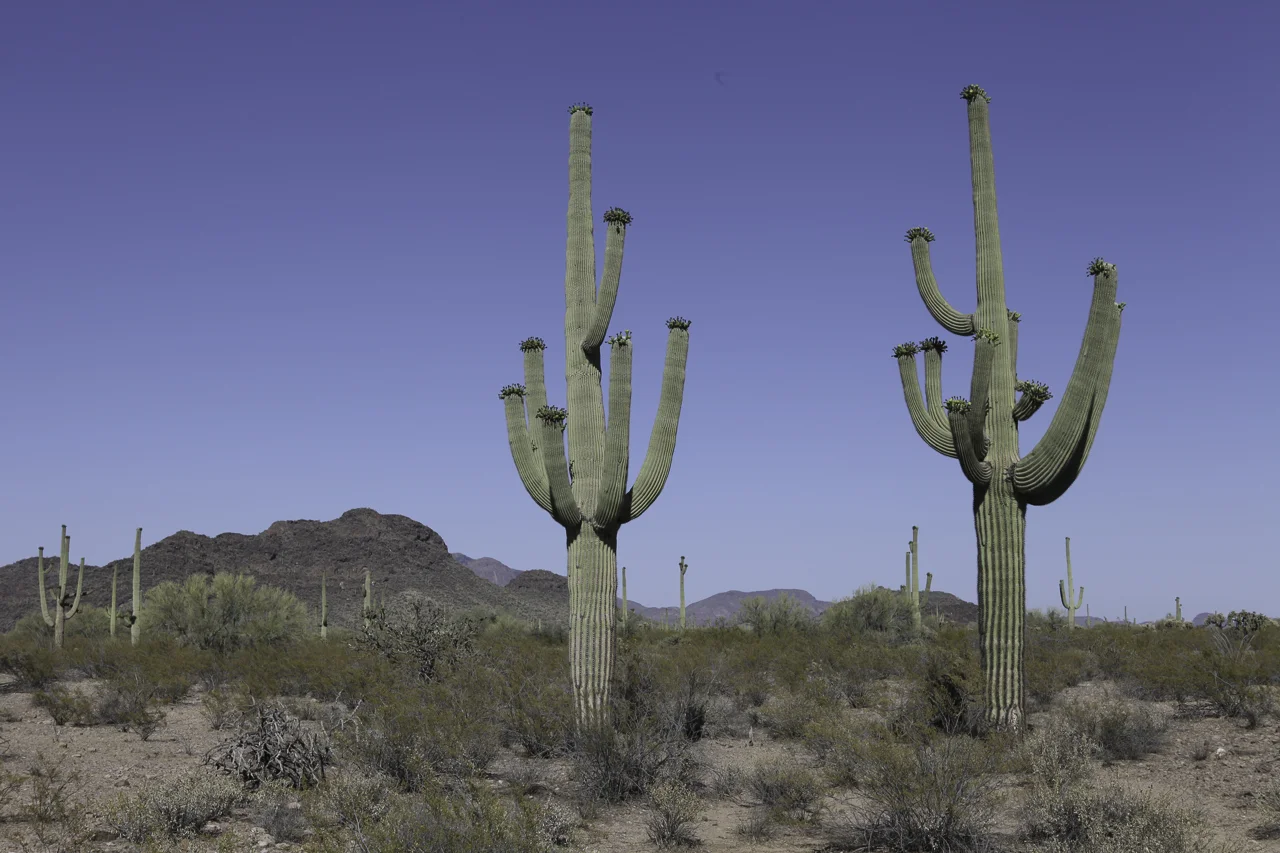

Recruitment windows are any period of time in which seeds germinate and grow into young plants successfully. Needless to say, they are a crucial component of of any plants' life cycle. For some species, these windows are huge, allowing them ample opportunity for successful reproduction. For others, however, these windows are small and specific. Take for instance the saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) of the American southwest. These arborescent cacti are famous the world over for their impressive stature. They are true survivors, magnificently adapted to their harsh, dry environment. This does not mean life is a cakewalk though. Survival, especially for seedlings, is measured by the slimmest of margins, with most saguaro dying in their first year.

Hot, dry days and freezing cold nights are not particularly favorable conditions for young cacti. As such, any favorable change in weather can lead to much higher rates of successful recruitment for a given year. Because of this, saguaro often grow up as cohorts that all took advantage of the same favorable conditions that tipped the odds in their favor. This creates an age pattern that researchers can then use to better understand the population dynamics of these cacti.

Recently, a researcher from York University noticed a particular pattern in the cacti she was studying. A large amount of the older cacti all dated back to the year 1884. What was so special about 1884, you ask? Certainly the climate must have been favorable. However, the real interesting part of this story is what happen the year before. 1883 saw the eruption of Krakatoa, a volcanic island located between Java and Sumatra. The eruption was massive, spewing tons of volcanic ash into the air. Effectively destroying the island, the eruption was so large that it was heard 1,930 miles away in western Australia.

The effects of the Krakatoa eruption were felt worldwide. Ash and other gases spewed into the atmosphere caused a chilling of the northern hemisphere. Records of that time show an overall cooling effect of more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit. In the American Southwest, this led to record rainfall from July 1883 to June 1884. The combination of higher than average rainfall and lower than average temperatures made for a banner year for saguaro cacti. Seedlings were able to get past that first year bottleneck. After that first year, saguaro are much more likely to survive the hardships of their habitat.

The Krakatoa eruption wasn't the only one with its own saguaro cohort. Further investigations have revealed similar patterns following the eruptions of Soufriere, Mt. Pelée, and Santa Maria in 1902, Ksudach in 1907, and Katmai in 1912. What this means is that conservation of species like the saguaro must take into account factors far beyond their immediate environment. Such patterns are likely not unique to saguaro either. The Earth functions as a biosphere and the lines we use to define the world around us can become quite blurry. If anything, this research underlines the importance of a system-based view. Nothing operates in a vacuum.

Photo Credit: Geir K. Edland