Photo by David Eickhoff licensed under CC BY 2.0

No, that's not dodder (Cuscuta sp.), its love vine (Cassytha filiformis), a member of the same family as the avacados in your kitchen (Lauraceae). It is a pantropical parasite that makes its living stealing water and nutrients from other plants. To do so, it punctures their vascular tissues with specialized structures called "haustoria." Amazingly, a recent observation made in Florida suggests that this botanical parasite may also be taking advantage of other parasites, specifically gall wasps.

Gall wasps are also plant parasites. They lay their eggs in developing plant tissues and the larvae release compounds that coax the plant to form nutrient-rich galls packed full of starchy goodness. Essentially you can think of galls as edible nursery chambers for the wasp larvae. While looking for galls on sand live oak (Quercus geminata) growing in southern Florida, Dr. Scott Egan and his colleagues noticed something odd. A small vine seemed to be attaching itself to the galls.

Love vine draping a host plant. Photo by Forest & Kim Starr licensed under CC BY 3.0

The vine in question was none other than love vine and they were attached to galls growing on the underside of the oak leaves. What is strange is that, of all of the places that love vine likes to attach itself to its host (new stems, buds, petioles, and on the top and edge of leaves), the only time this vine showed any "interest" in the underside of oak leaves was when galls were present. Obviously this required further investigation.

The team discovered that at least two different species of gall wasps were being parasitized by love vine - one that produces small, spherical galls on the underside of oak leaves and one that forms large, multi-chambered galls on oak stems. Upon measuring the infected and uninfected galls, the team discovered that there were significant differences that could have real ecological significance.

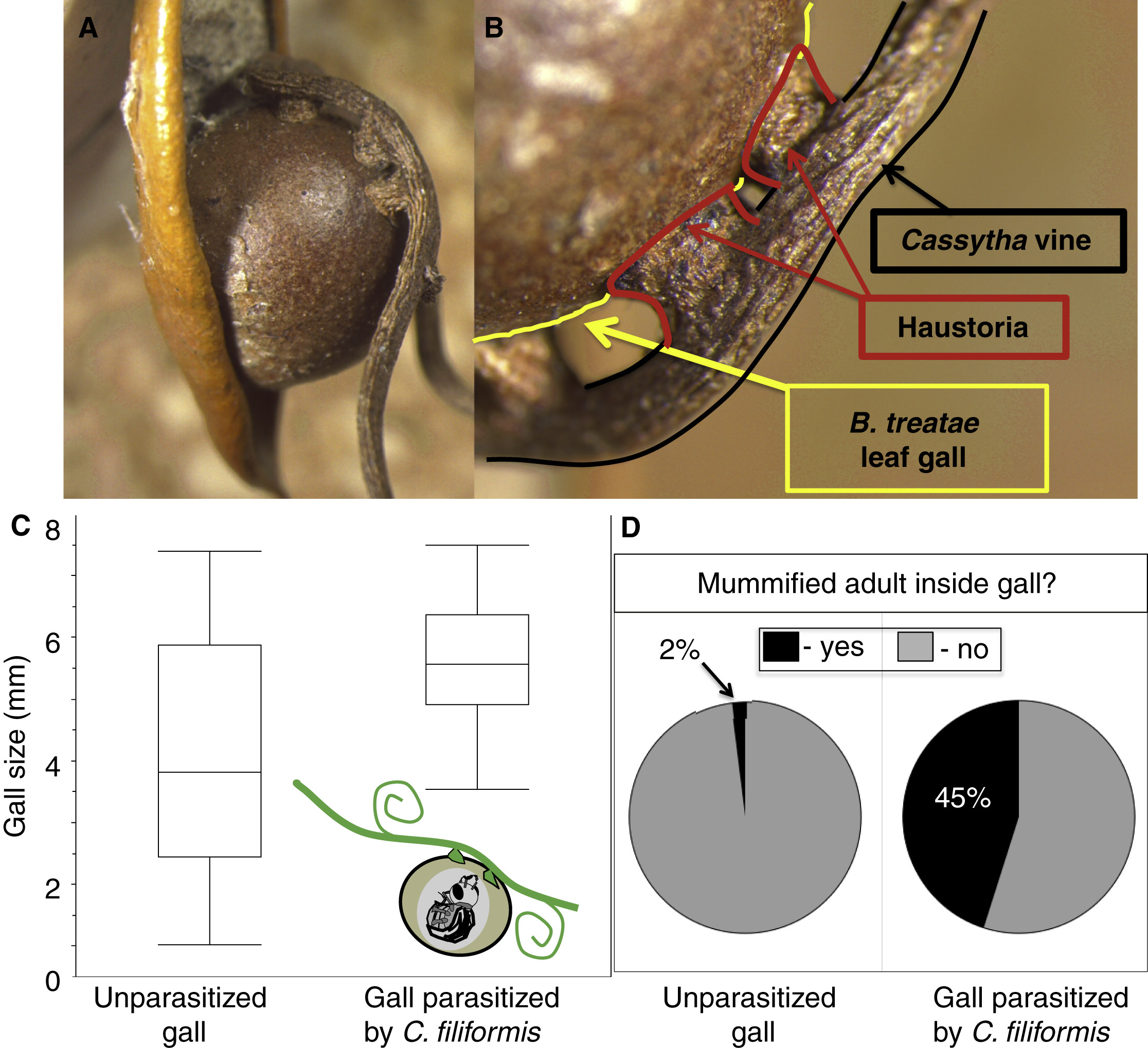

(A) Cassytha filiformis vine attaching haustoria to a leaf gall induced by the wasp Belonocnema treatae on the underside of their host plant, Quercus geminata. (B) Labeled graphic of insect gall, parasitic vine, and vine haustoria. (C) Box plots of leaf gall diameter for unparasitized galls (control) and galls that have been parasitized by C. filiformis. (D) Proportion of B. treatae leaf galls that contained a dead ‘mummified’ adult for unparasitized galls (control) and galls that have been parasitized by the vine C. filiformis. [SOURCE]

For the spherical gall wasp, infected galls tended to be much larger, however, the team feels that this may actually be due to the fact that the vine "prefers" larger galls. Astonishingly, larvae living in the infected galls were 45% less likely to survive. For the multi-chambered gall wasp, infection by love vine was associated with a 13.5% decrease in overall gall size. They suggest this is evidence that love vine is having net negative impacts on these parasitic wasps.

Subsequent investigation revealed that these wasps were not alone. In total, the team found love vine attacking the galls of at least two other wasps and one species of gall-making fly (though no data were reported for these cases). To be sure that love vine was in fact parasitizing these galls, they needed to have a closer look at what the vine was actually doing.

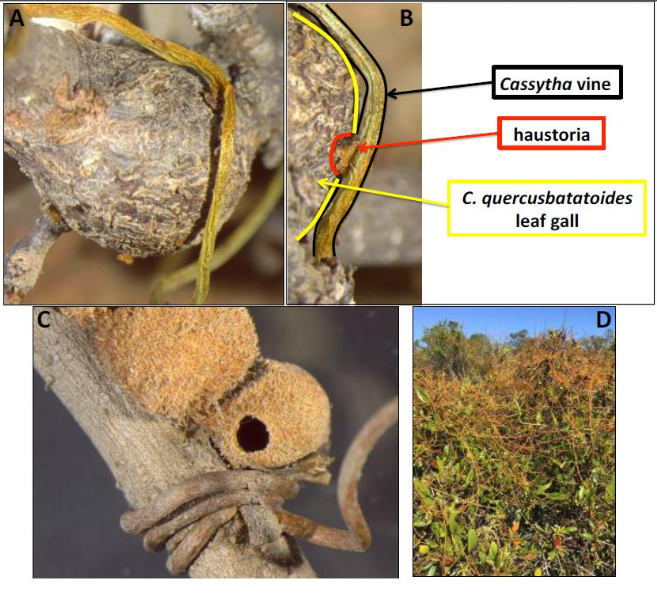

Figure S2. (A) Cassytha filiformis vine attaching haustoria to a leaf gall induced by the wasp Callirhytis quercusbatatoides on the stem of their host plant, Quercus geminata. (B) Labeled graphic of insect gall, parasitic vine, and vine haustoria on C. quercusbatatoides. (C) Exemplar of parasitic vine wrapping tightly around the stem directly proximate to a gall induced by the wasp Disholcaspis quercusvirens on Q. geminata. (D) Field site where love vine, C. filiformis, is attacking the sand live oak, Q. geminata, and many of the gall forming wasps on the same host plant. [SOURCE]

Dissection of the galls revealed that the haustoria were plugged into the gall itself, not the wasp larvae. However, because the larvae simply cannot develop without the nutrients and protection provided by the gall, Eagan and his colleagues conclude that these do indeed represent a case of a parasite being parasitized by another parasite.

At this point, the next question that must be asked is how common is this in love vine or, for that matter, across all other parasitic plants that utilize haustoria. Considering that parasites of parasites are nothing new in the biosphere, it is a safe bet that this will not be the last time this phenomenon is discovered.

Photo Credits: [1] [2] [3] [4]

Further Reading: [1]