Photo by Geoff McKay licensed under CC BY 2.0

Bat plants (genus Tacca) are bizarre-looking plants. Their nondescript appearance when not in flower enshrouds the extravagant and, dare I say macabre appearance of their blooms. The inflorescence of this genus is something to marvel at. The flowers are borne above sets of large, conspicuous bracts and numerous whisker-like bracteoles. Despite their unique appearance and popularity among plant collectors, the pollination strategies utilized by the roughly 20 species of bat plants have received surprisingly little attention over the years.

Bat plants are most at home in the shaded, humid understories of tropical rainforests around the globe (though there are a couple exceptions to this rule). Amazingly, these plants are members of the yam family (Dioscoreaceae) and are thought to be closely related to the equally bizarre Burmanniaceae, a family comprised entirely of oddball parasites. Taxonomic affinities aside, there is no denying that bat plants produce truly unique inflorescences and many a hypotheses has been put forth to explain the function of their peculiar floral displays.

The white bat plant (Tacca integrifolia). Photo by MaX Fulcher licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The black bat plant (Tacca chantrieri). Photo by Hazel licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The most common of these is that the flowers are an example of sapromyiophily and thus mimic a rotting corpse in both smell and appearance as a means of attracting carrion flies. However, despite plenty of speculation, such hypotheses have largely gone untested. It wasn’t until fairly recently that anyone put forth an attempt to observe pollination of these plants in their natural habitats.

A) T. leontopetaloides; (B) T. plantaginea; (C) T. parkeri; (D) T. palmatifida; (E) T. palmata; (F) T. subflabellata; (G) T. integrifoliafrom; (H) T. integrifoliafrom; (I) T. ampliplacenta; (J) T. chantrieri. [SOURCE]

A 2005 study done in South Yunnan province, China found that almost nothing visited the flowers of Tacca chantrieri. Despite the presence of numerous potential pollinators, only a handful of small, stingless bees paid any attention to these obvious floral cues. This led the authors to suggest that most bat plants are self-pollinated. Indeed, genetic analysis of different populations of T. chantrieri helped bolster this conclusion by demonstrating that there is very little evidence of genetic transfer between T. chantrieri populations. Yet, this is far from a smoking gun. Strong genetic structuring among populations could simply mean that pollinators aren’t moving very far. Also, if most bat plants simply opt for fertilizing their own blooms, why has this genus maintained such elaborate floral morphology? Needless to say, more work was needed.

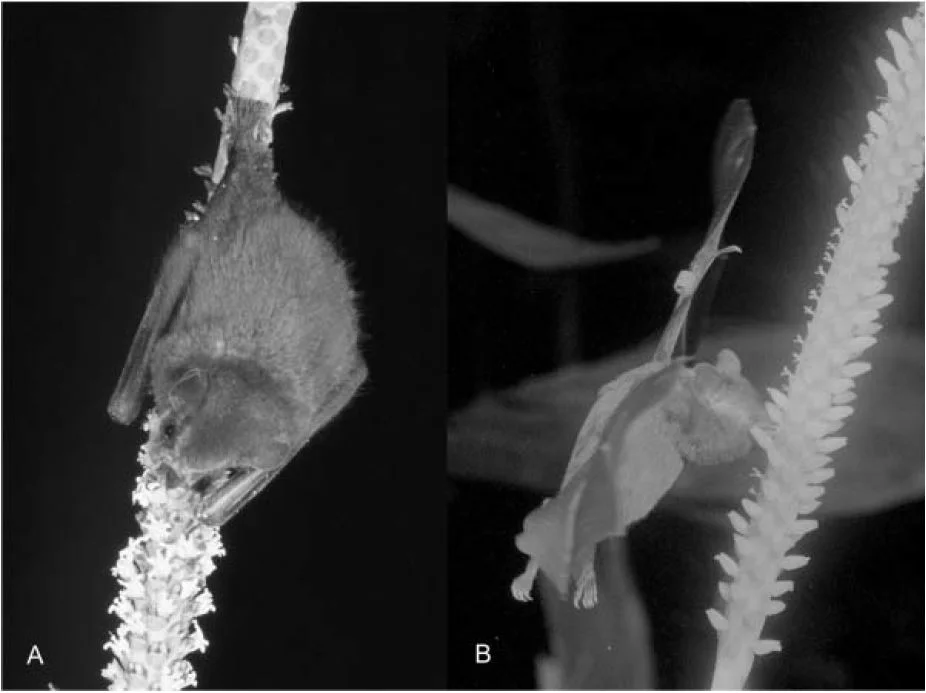

Luckily, a recent study from Malaysia has made great strides in our understanding of the sex lives of these plants. By observing 7 different species of bat plant in the wild, researchers were able to collect plenty of data on bat plant pollination. It turns out that the flowers of these 7 species are quite popular with insects. Bat plant floral visitors in their study included everything from tiny, stingless bees to ants, beetles, and weevils. However, the most common floral visitors for most bat plant species were small, biting midges. This is where things get very interesting.

(A–C) Female Forcipomyia biting midge. Arrows indicating pollen grains. [SOURCE]

As their common name suggests, biting midges are most famous for biting other animals. Though they will drink nectar, female biting midges need lots of protein to successfully produce eggs. They meet their protein needs by drinking the blood of insects and mammals. Of the biting midges that most frequently visited bat plant flowers, the most common hail from two groups known to feed exclusively on mammalian blood. Finding these biting midges in high numbers on bat plant flowers raises the question of what they stand to gain from these strange-looking blooms.

The conclusion the authors came to was that bat plant blooms are using a bit of trickery to lure in female midges. They hypothesize that the color patterns of the bracts and flickering motion of whisker-like bracteoles simulates the movements of mammals that the midges normally feed on. It is also possible that bat plant flowers emit volatile scents that enhance this mimicry, though more work is needed to say for sure. What the researchers do know is that the behavior of female biting midges upon visiting a flower is enough to pick up and deposit plenty of pollen as they search for a blood meal that doesn’t exist. How common this floral ruse is among the remaining species is yet to be determined but the similarities in inflorescence structure among members of this genus suggest similar tricks are being played on pollinators wherever bat plants grow.

![(A–C) Female Forcipomyia biting midge. Arrows indicating pollen grains. [SOURCE]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/544591e6e4b0135285aeb5b6/1602516996716-ICQ7PIZDYU1BOSTTEWJ3/tacca+midge.JPG)